16 Poemas Después de la Muerte -- Poems by Héctor González

Poems in Spanish with English translations by Héctor González.

Hello!

Today I have a really cool project to share! This is the latest thing my subscribers and patrons have sponsored. It was exclusive to them until the 21st of June, 2021, and now it’s time to share it with the world for free! If you think this kind mode of story and poem sharing is cool, consider subscribing here or become a paid subscriber!

This is the second of my two Texas creator pieces. The first was a story by Allison Thai. I came up with the idea to ask specifically Texan creators back when Texas was facing major ice storms and crumbling energy infrastructure. I wanted to send a little money directly to Texan creators AND to donate to a charitable organization they personally found meaningful. Of course as time passed the ice storms and the acute crisis related to them was over, but Texas still has plenty of things it could use help with. Allison specifically asked for my matching fund to go to the VCSA, an organization for Vietnamese immigrants in Texas, and Héctor asked for my matching funds to go to RAICES.

Here’s what Héctor has to say about RAICES:

RAICES is an organization constantly fighting for immigrant families. Since the start of the concentration camps in the border, their team has fought to help all the immigrants, protecting their human rights. I truly believe in their compassionate efforts.

If you enjoy these poems, do consider making a donation of your own!

You can listen to Héctor read each of these poems and give a few extras in the podcast episode.

Listen to "16 Poemas Después de la Muerte --Poems by Héctor González" on Spreaker.16 Poemas Después de la Muerte

by Héctor González

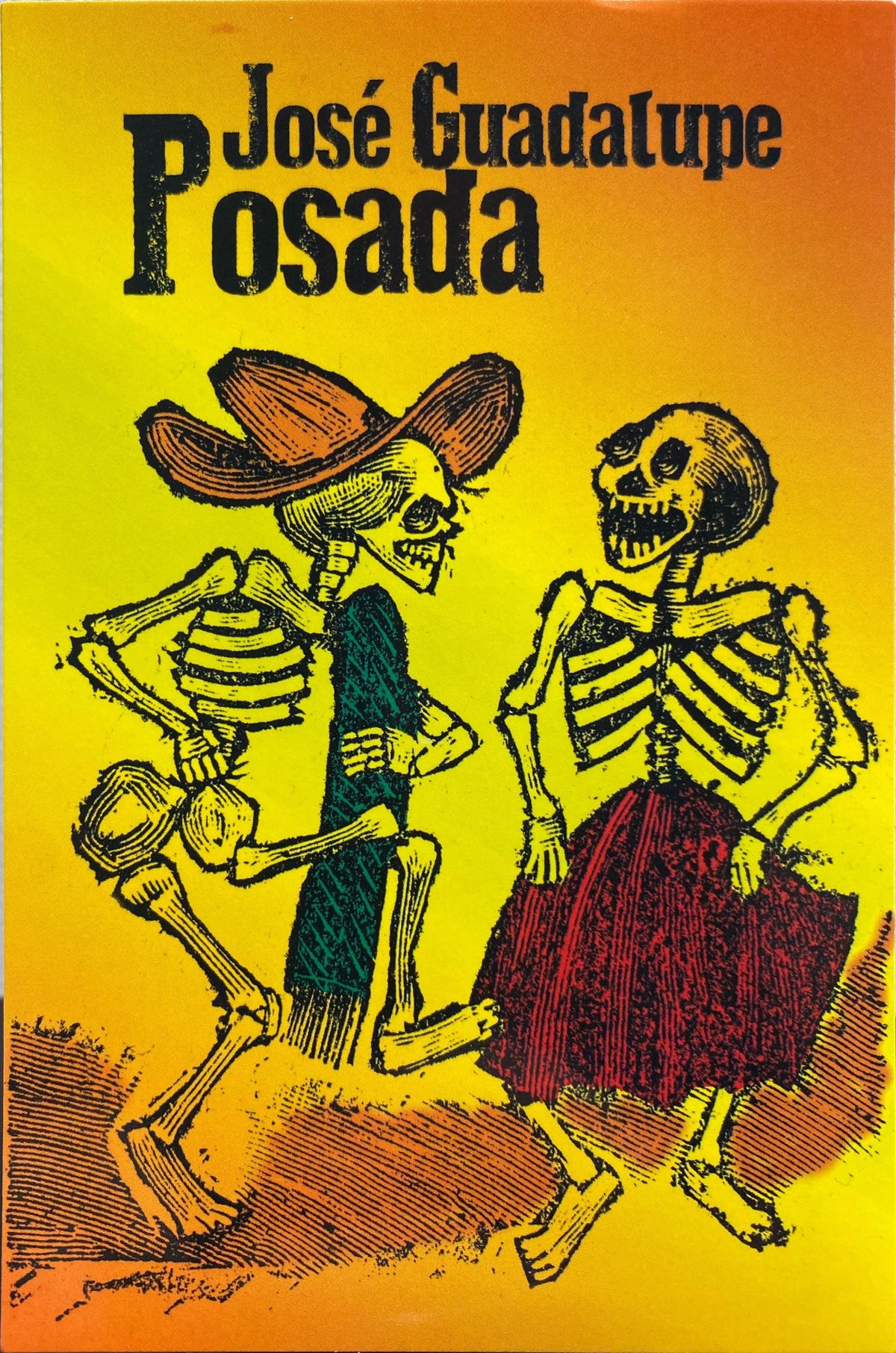

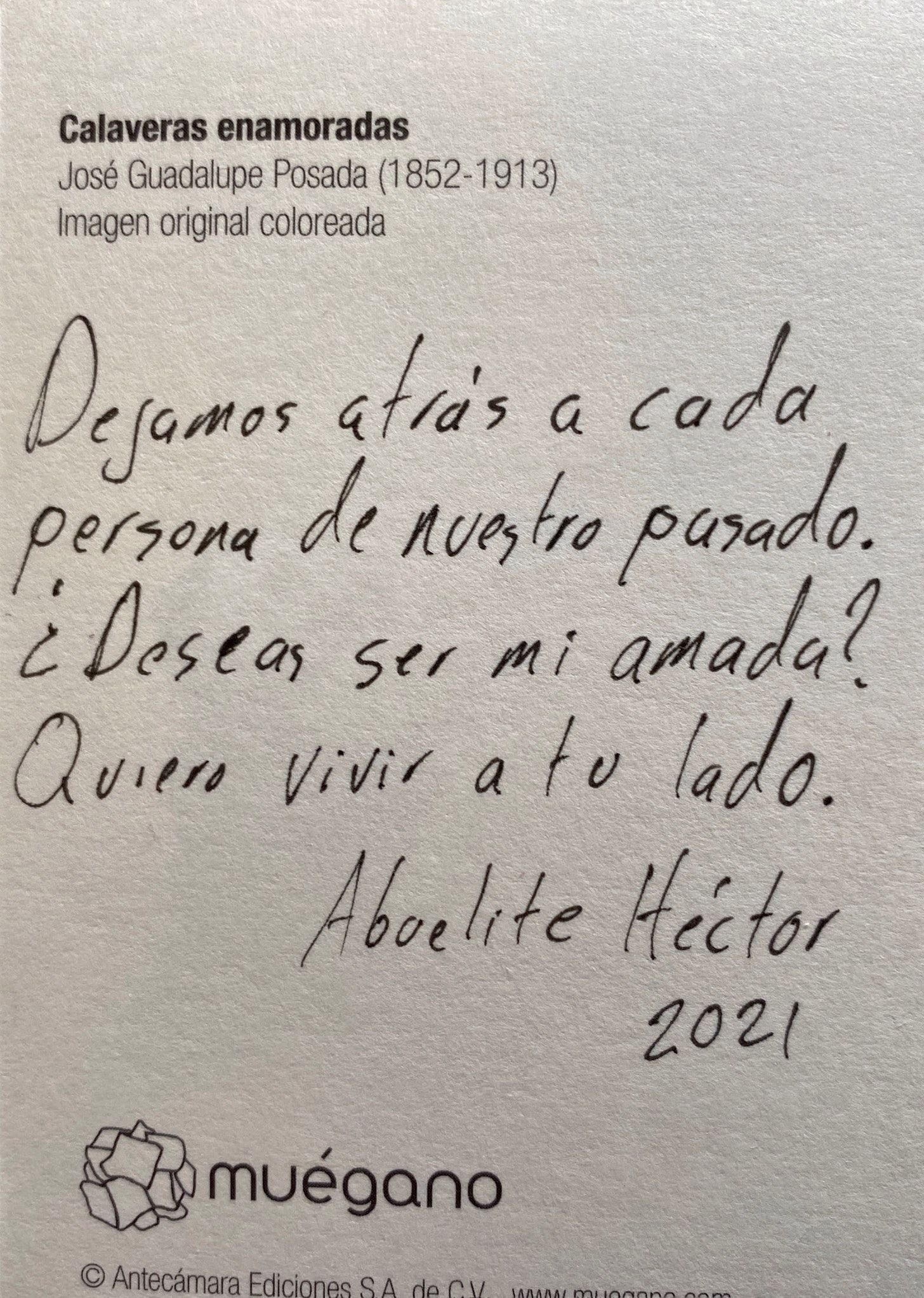

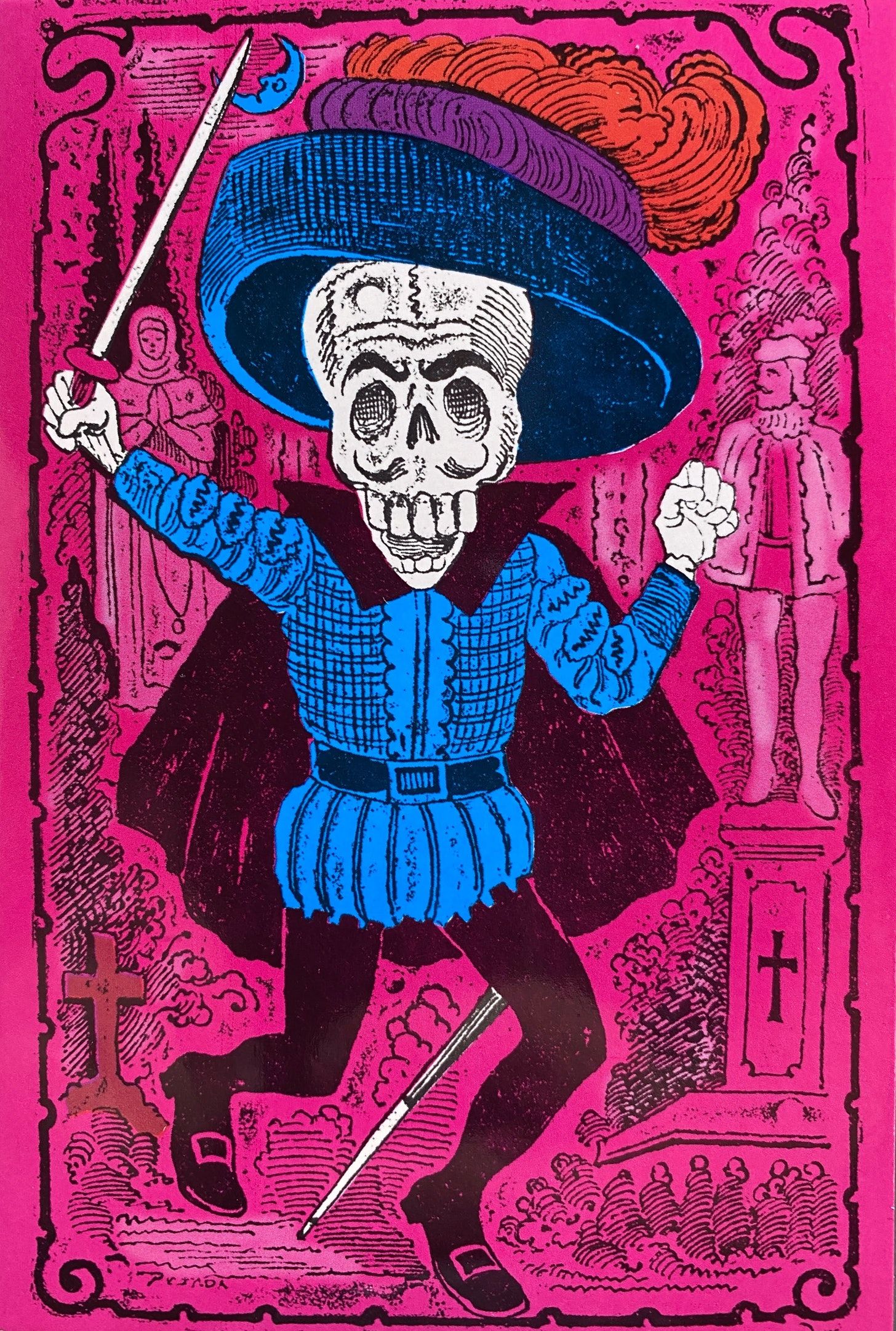

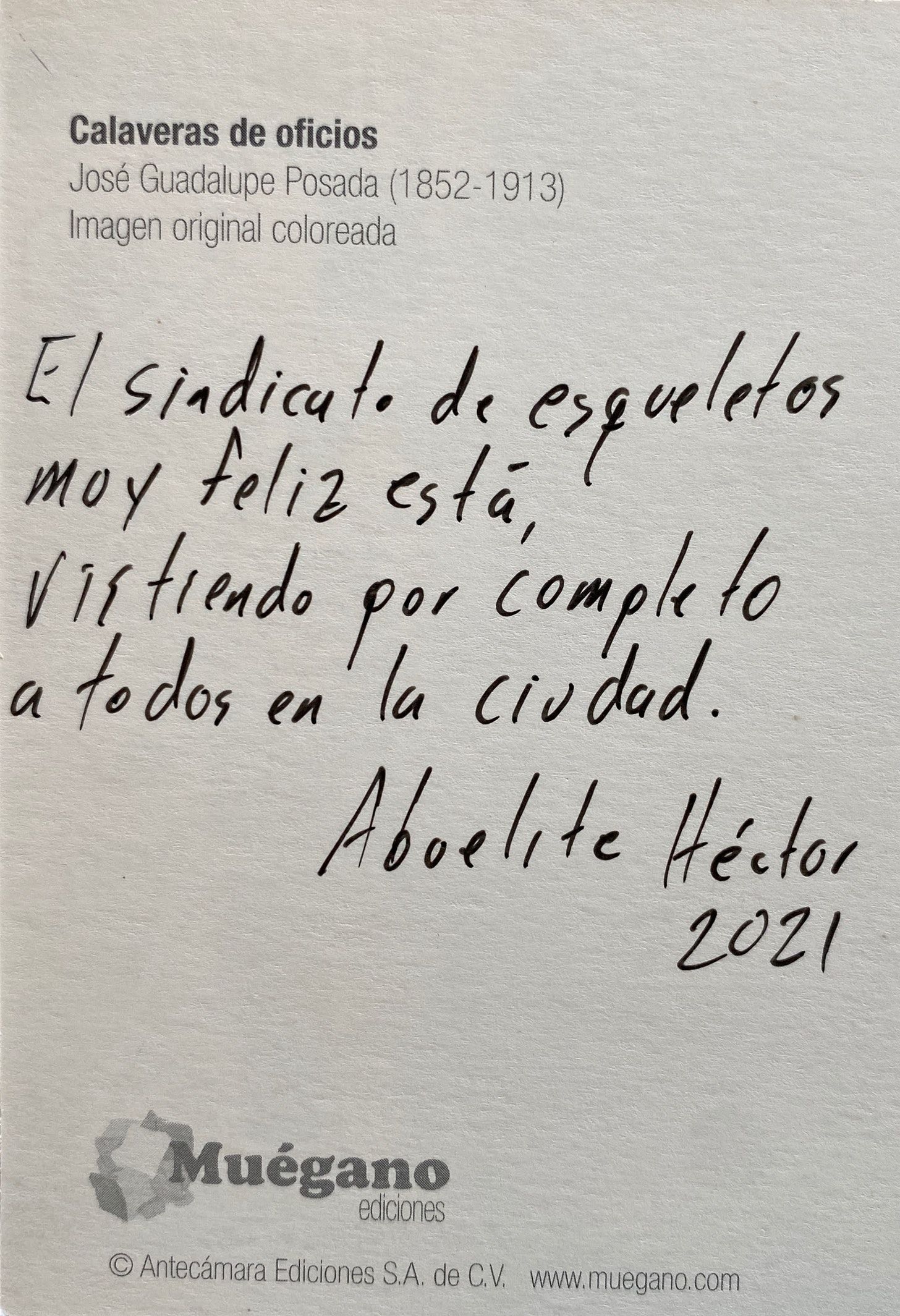

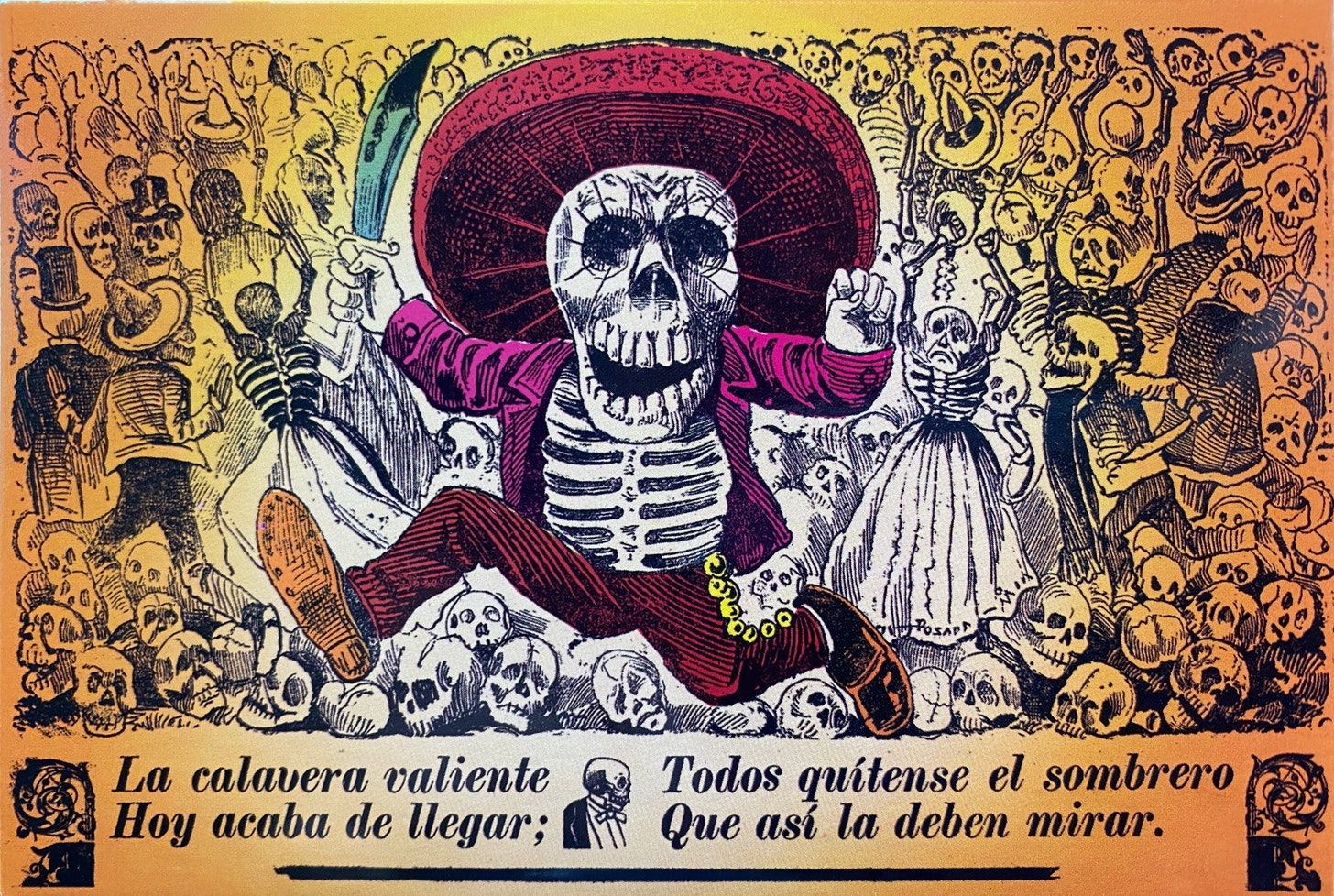

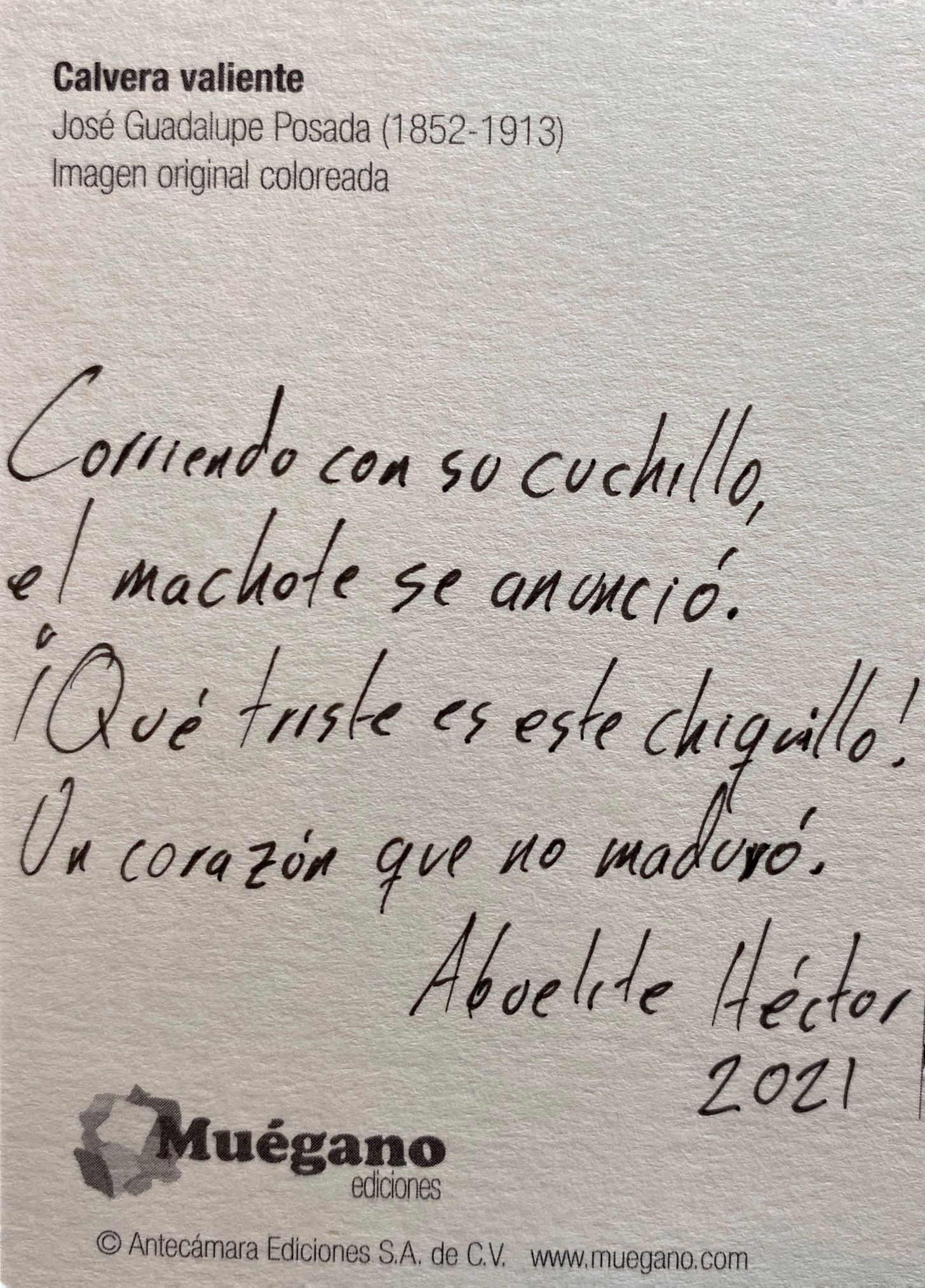

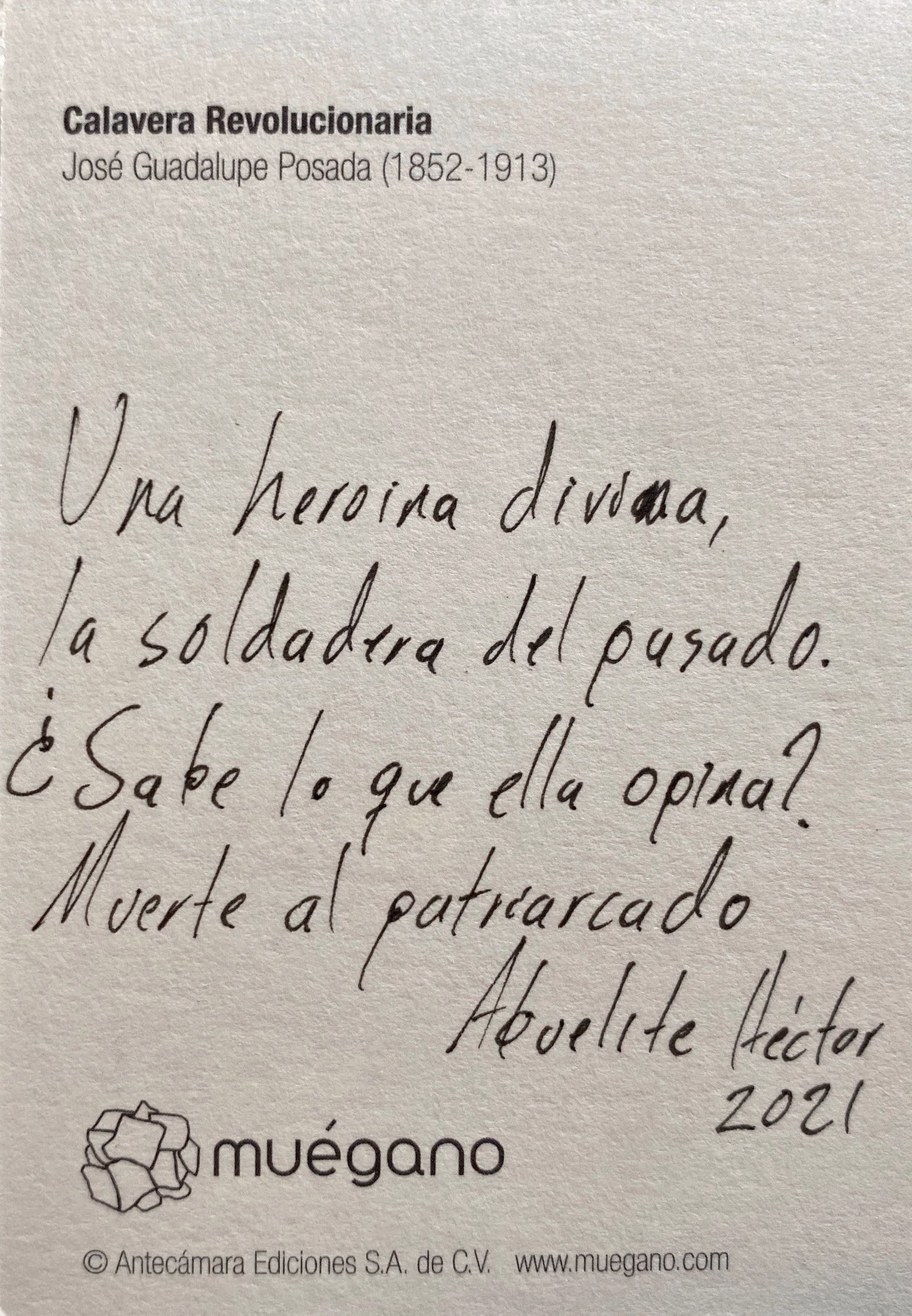

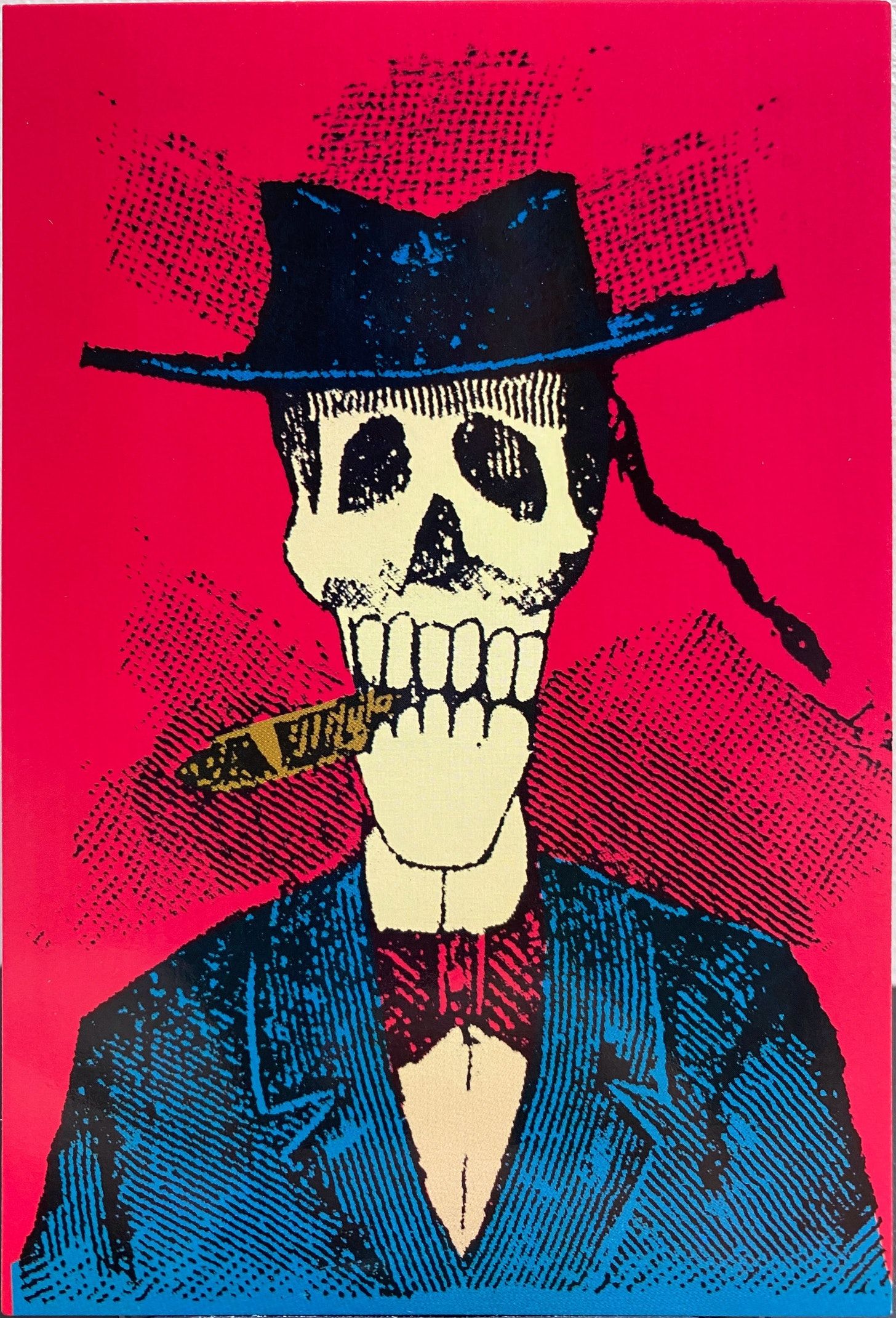

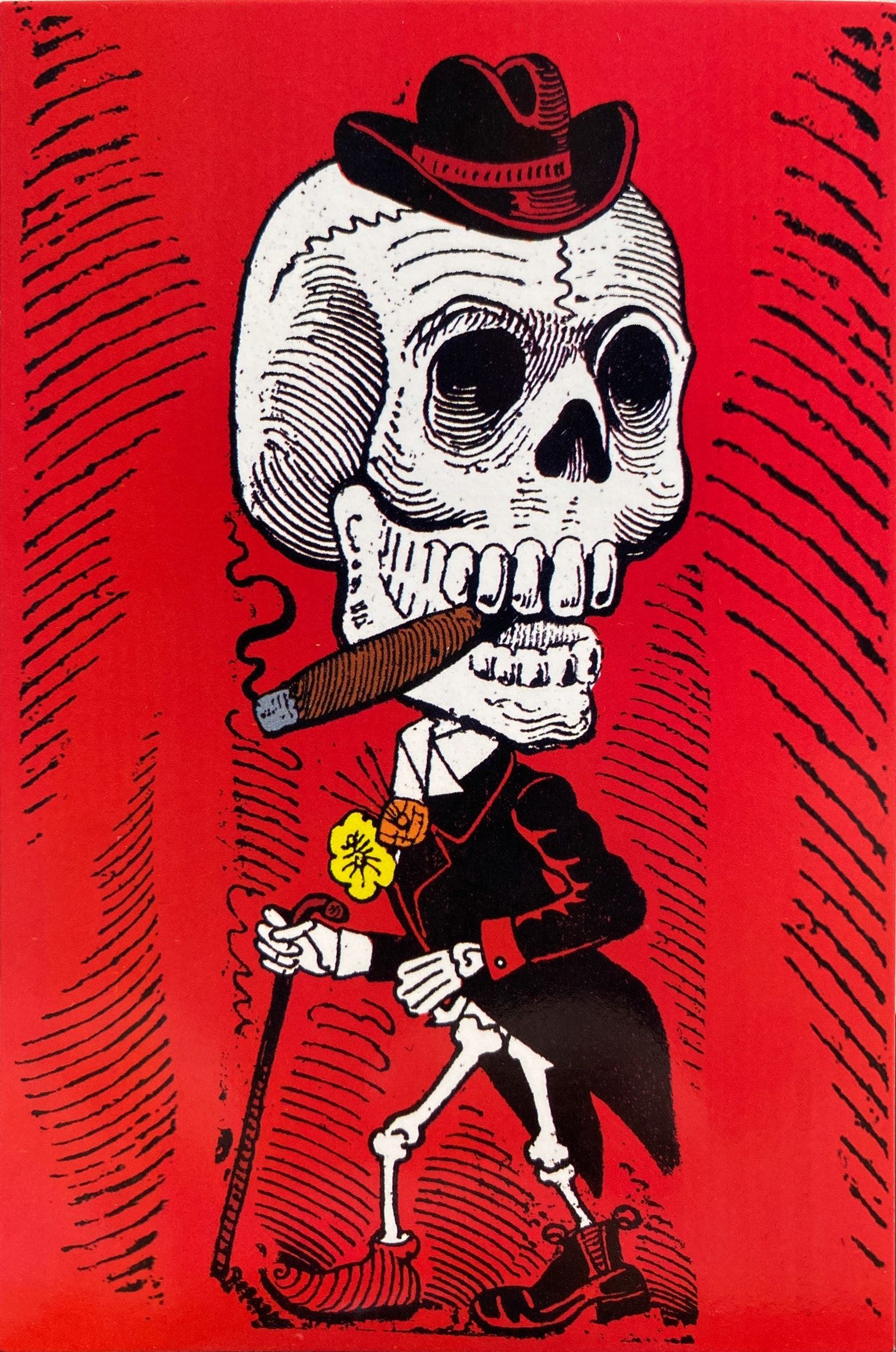

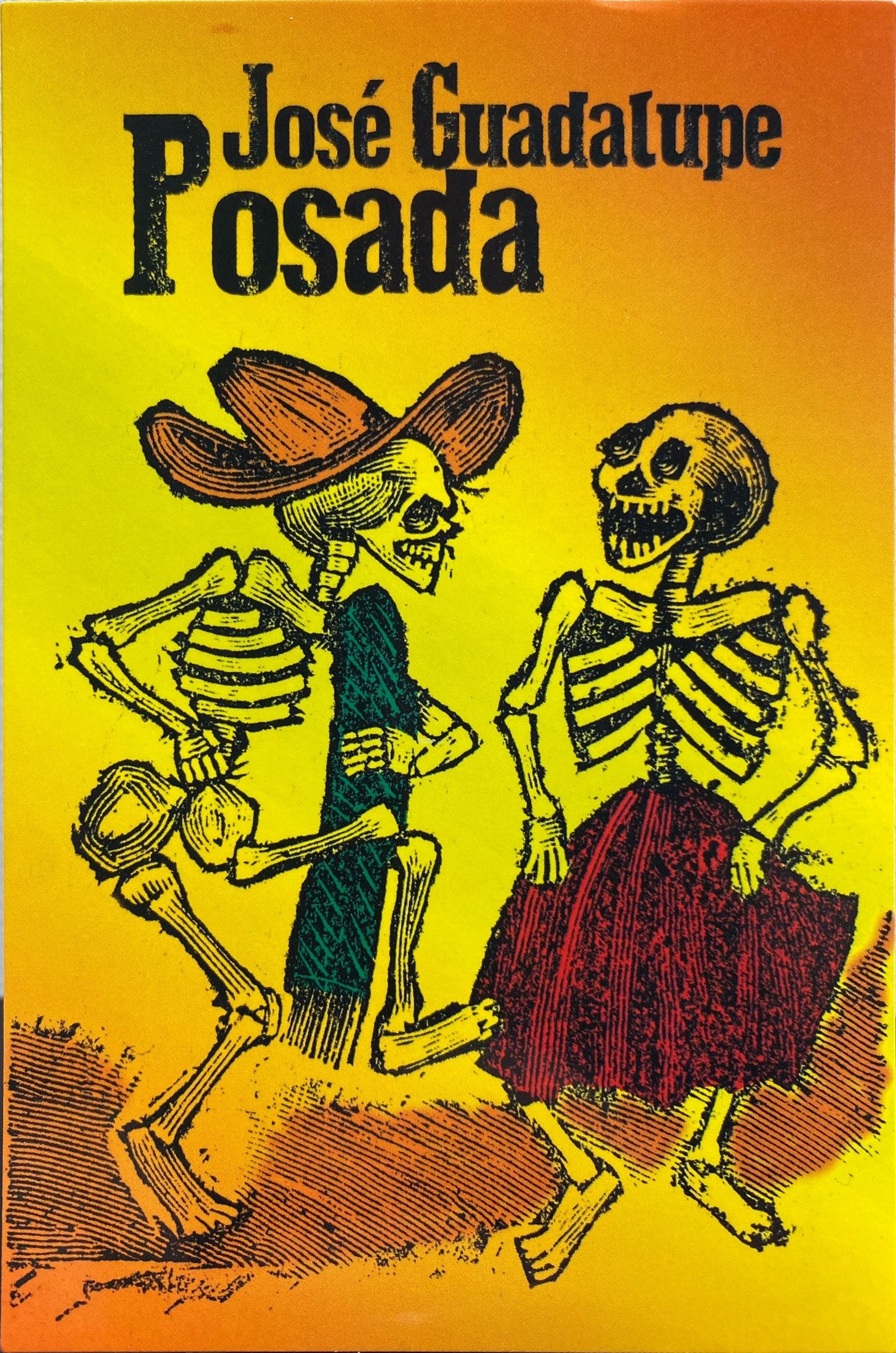

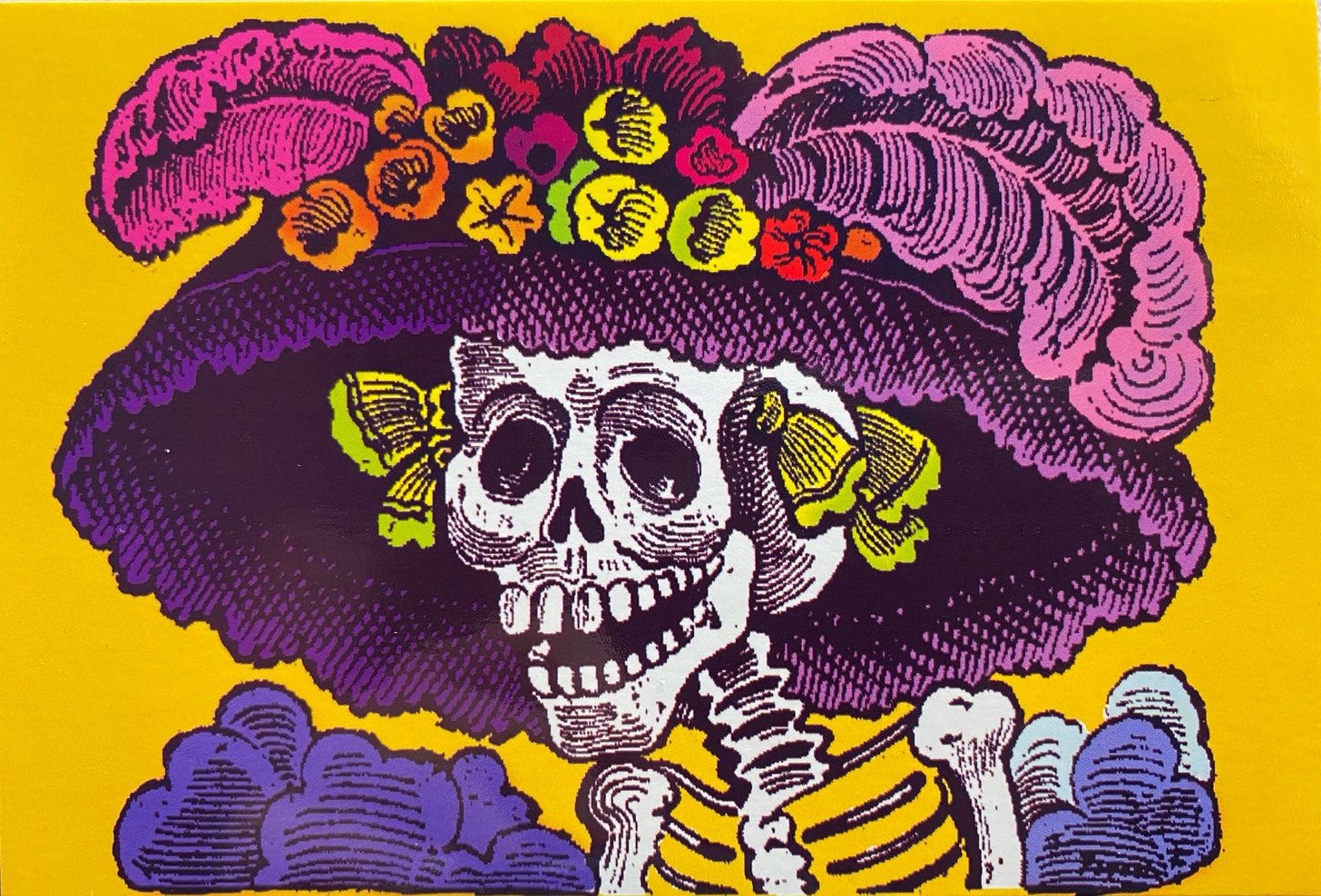

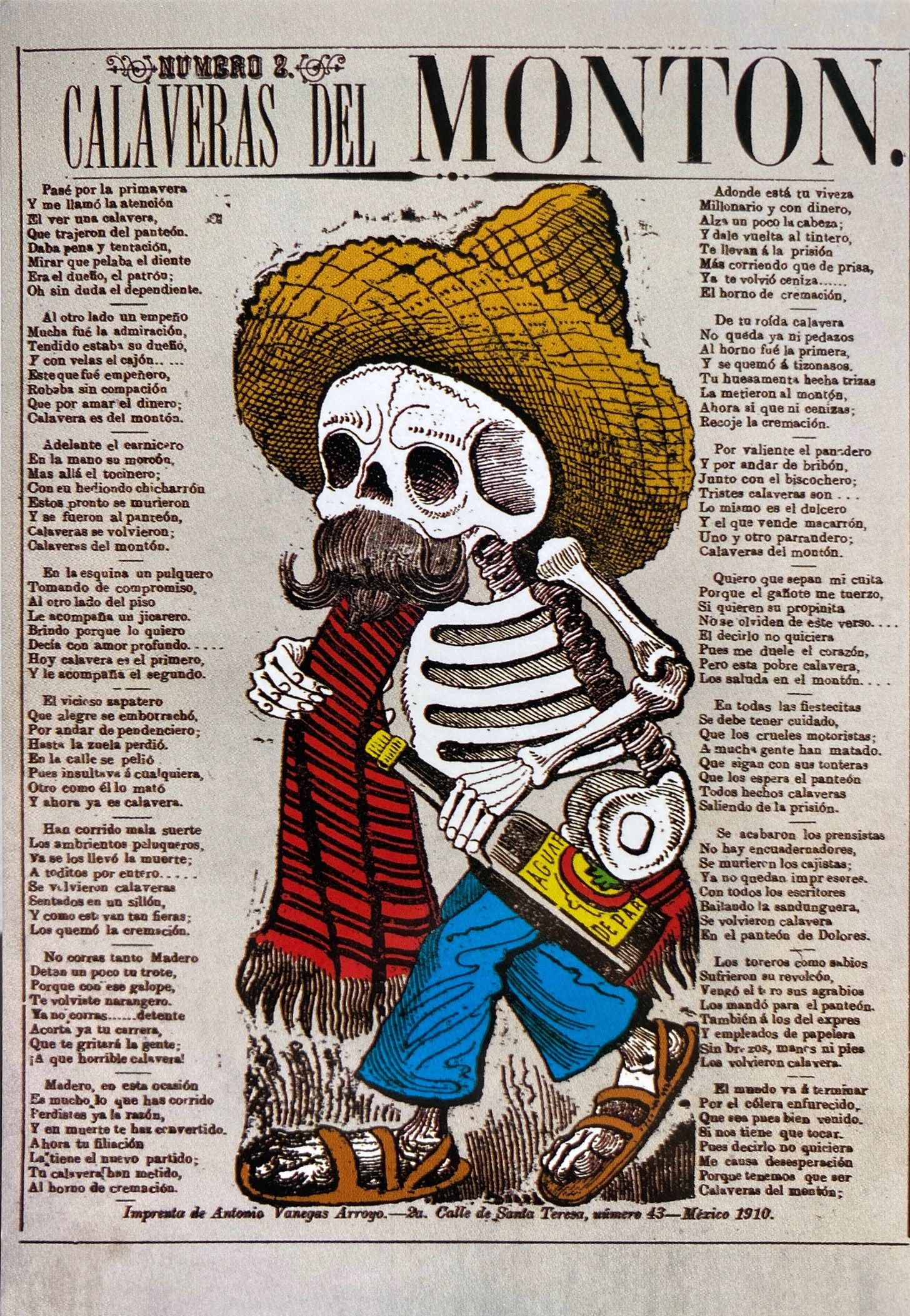

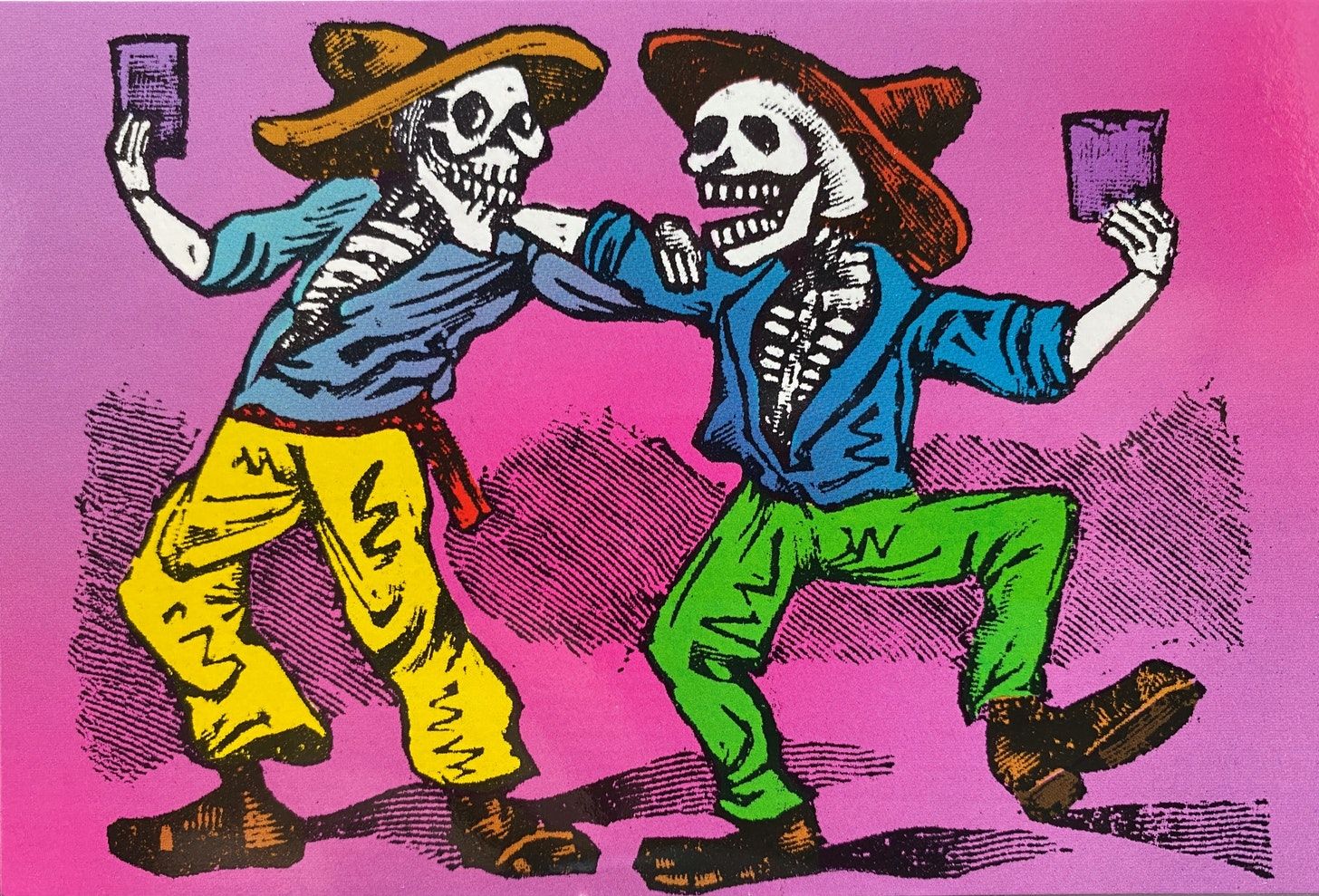

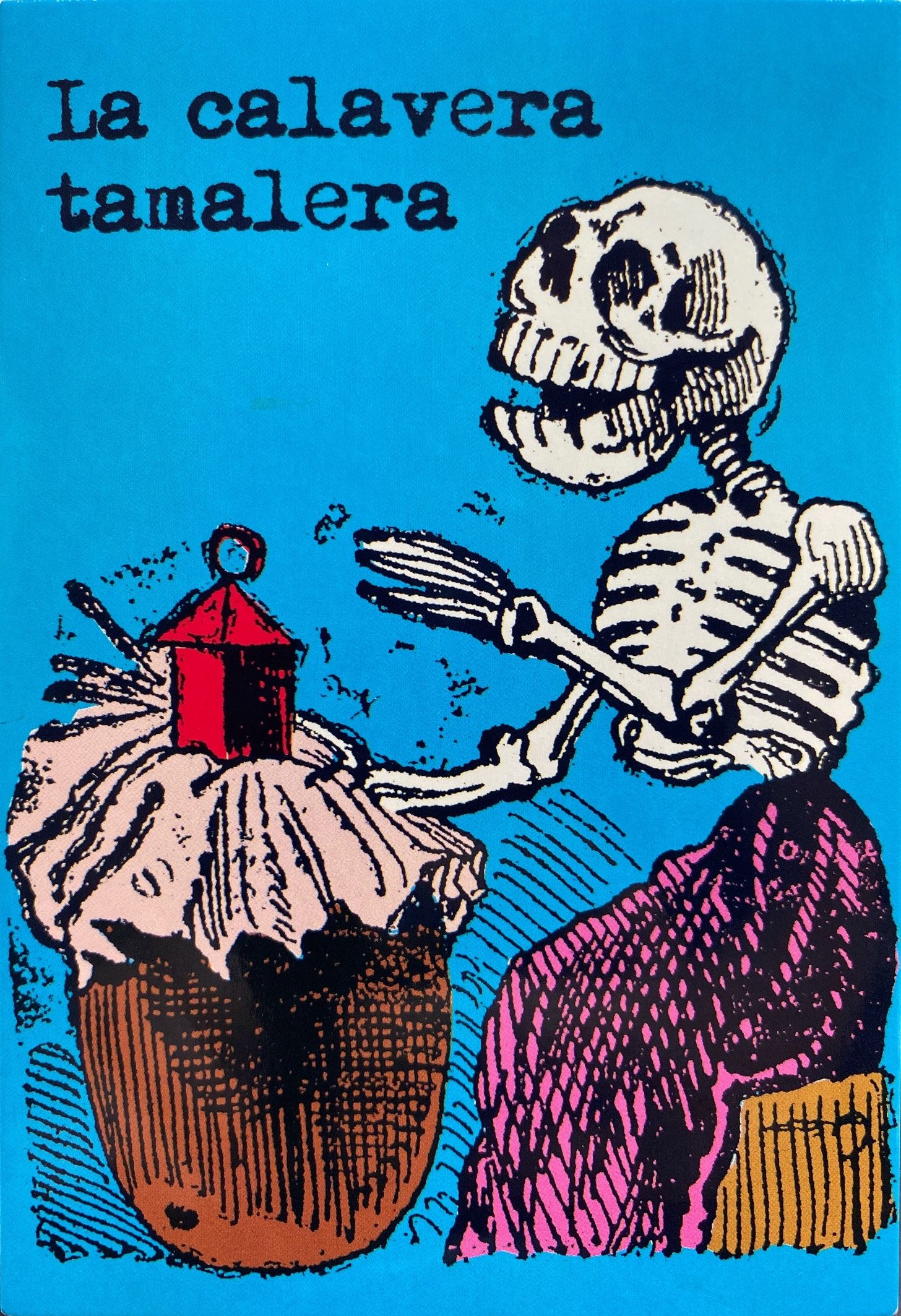

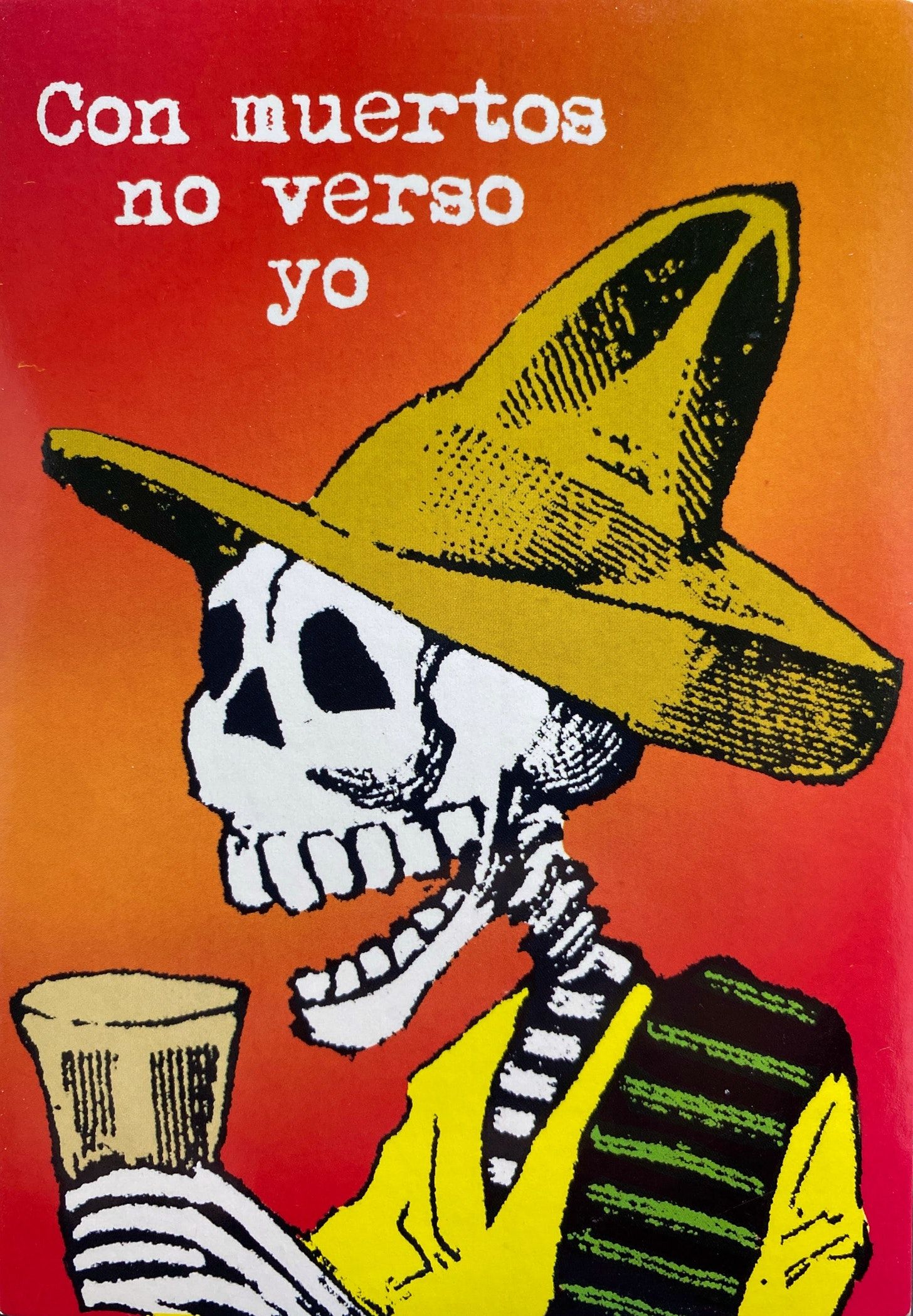

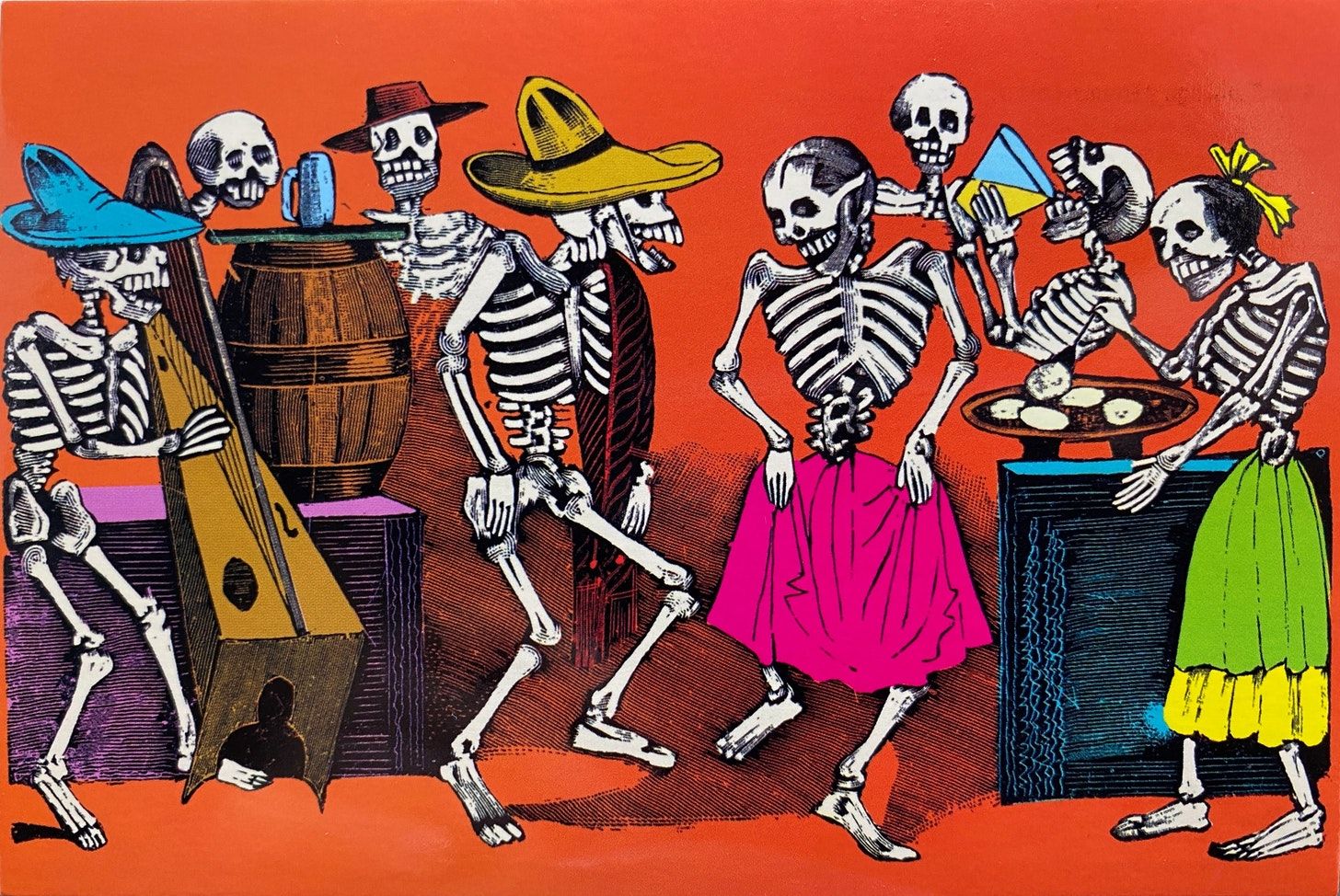

On my last trip to Mexico City, I found these postcards with the art of José Guadalupe Posada. These images depict skeletons, not as frozen reminders of our mortality but as vivacious and lively entities. Posada’s art celebrated our dearly departed as the people we knew. His work would influence Diego Rivera and lead to the iconic calavera catrina.

In México, we see death not as finality but another path in a person’s life. We mourn, but we also celebrate. We regularly joke about our final day. One of the most imaginative traditions around our Día de Muertos celebration are calaveras, rhymes with fun themes, where we create scenarios about the death of others. Sounds grim? These are very tongue in cheek with insights on the person “memorialized.”

Partially inspired by calaveras, I chose a postcard at random. I saw the image and created a small poem. I did this across a series of days. I sent these also to many friends. Some expect these, some will not.

In a year where we all have either experienced or seen tremendous loss, some of us grieve with stories.

1

Dejamos atrás a cada

persona de nuestro pasado.

¿Deseas ser mi amada?

Quiero vivir a tu lado

Translation to English:

We leave behind each

person from our past.

Do you want to be my beloved?

I want to live with you

2

Un tenorio yo fui

hiriendo los corazones,

mas yo nunca conocí

a quien calmara mis pasiones.

Translation to English:

A tenorio I was

wounding hearts,

but I never knew

who will calm my passions.

3

El sindicato de esqueletos

muy feliz esta,

vistiendo por completo

a todos en la ciudad.

Translation to English:

The Skeleton Union

Was full of joy,

they were making clothes

everyone in town.

4

Corriendo con su cuchillo

el machote se anunció.

¡Qué triste es este chiquillo!

Un corazón que no maduró.

Translation to English:

Running with his knife

the macho was announced his arrival.

Sad little boy!

A heart that did not mature.

5

Una heroina divina,

la soldadera del pasado.

¿Sabe lo que ella opina?

Muerte al patriarcado.

Transation to English:

A divine heroine,

the soldadera of the past.

Do you know what she thinks?

Death to the patriarchy.

6

“El tabaco no me mató,”

me dijo mi abuelo.

“Lo que la vida me arrebató

llenó de tristeza mi duelo.”

Translation to English:

"Tobacco didn't kill me,"

my grandfather told me.

"What life took from me

has filled my grief with sadness."

7

Me enterraron vistiendo elegante

pues siempre he sido importante.

¿Por qué mi cráneo es gigante?

Guarda mi ego, que es abundante.

Translation to English:

They buried me wearing fancy clothes

as I’ve always been important.

Why is my skull so huge?

To store my ego, which is abundant.

8

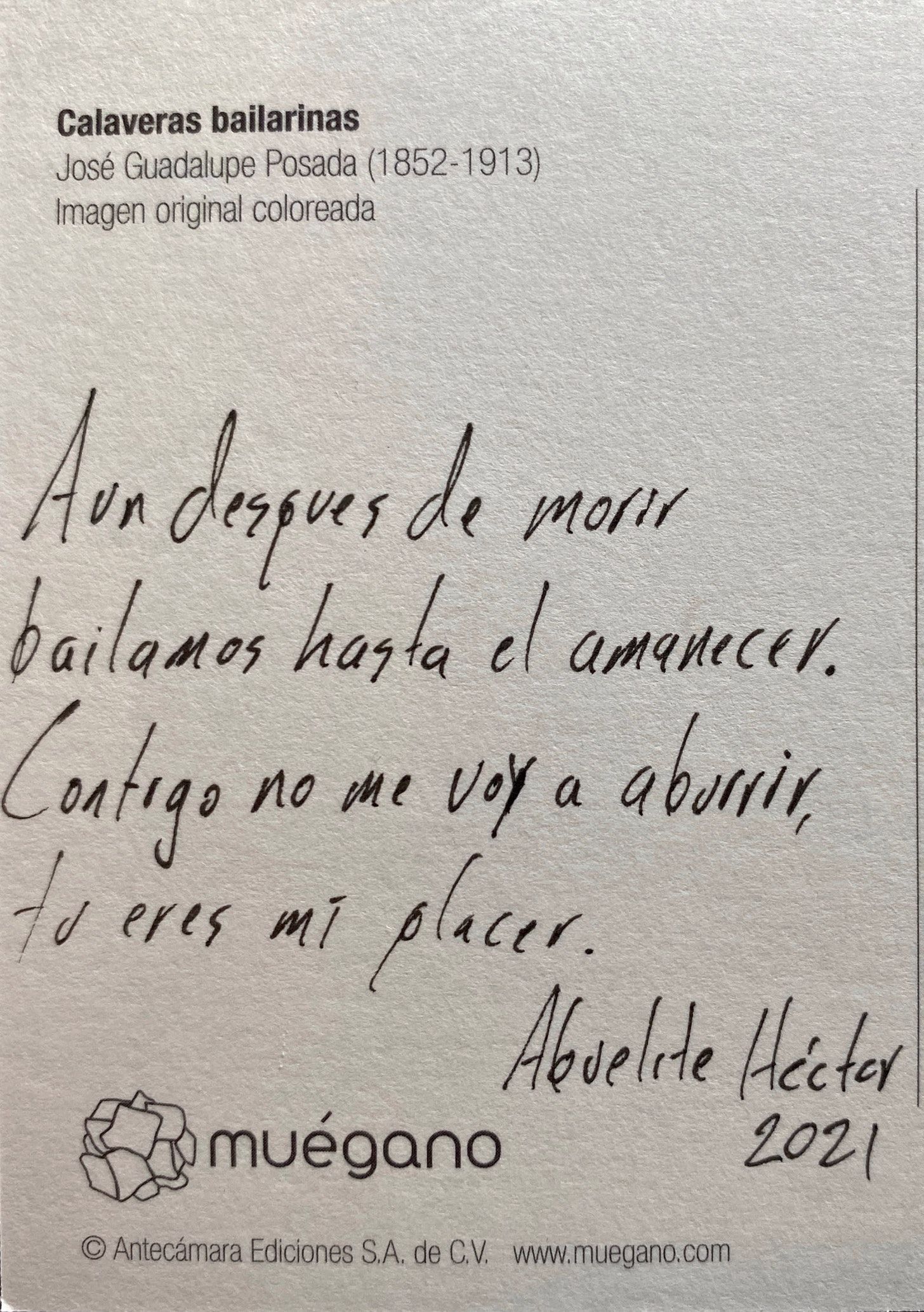

Aun después de morir

bailamos hasta el amanecer.

Contigo no me voy a aburrir,

tu eres mi placer.

Translation to Enligsh:

Even after dying

we dance until dawn.

I will not get bored with you,

you are my pleasure.

9

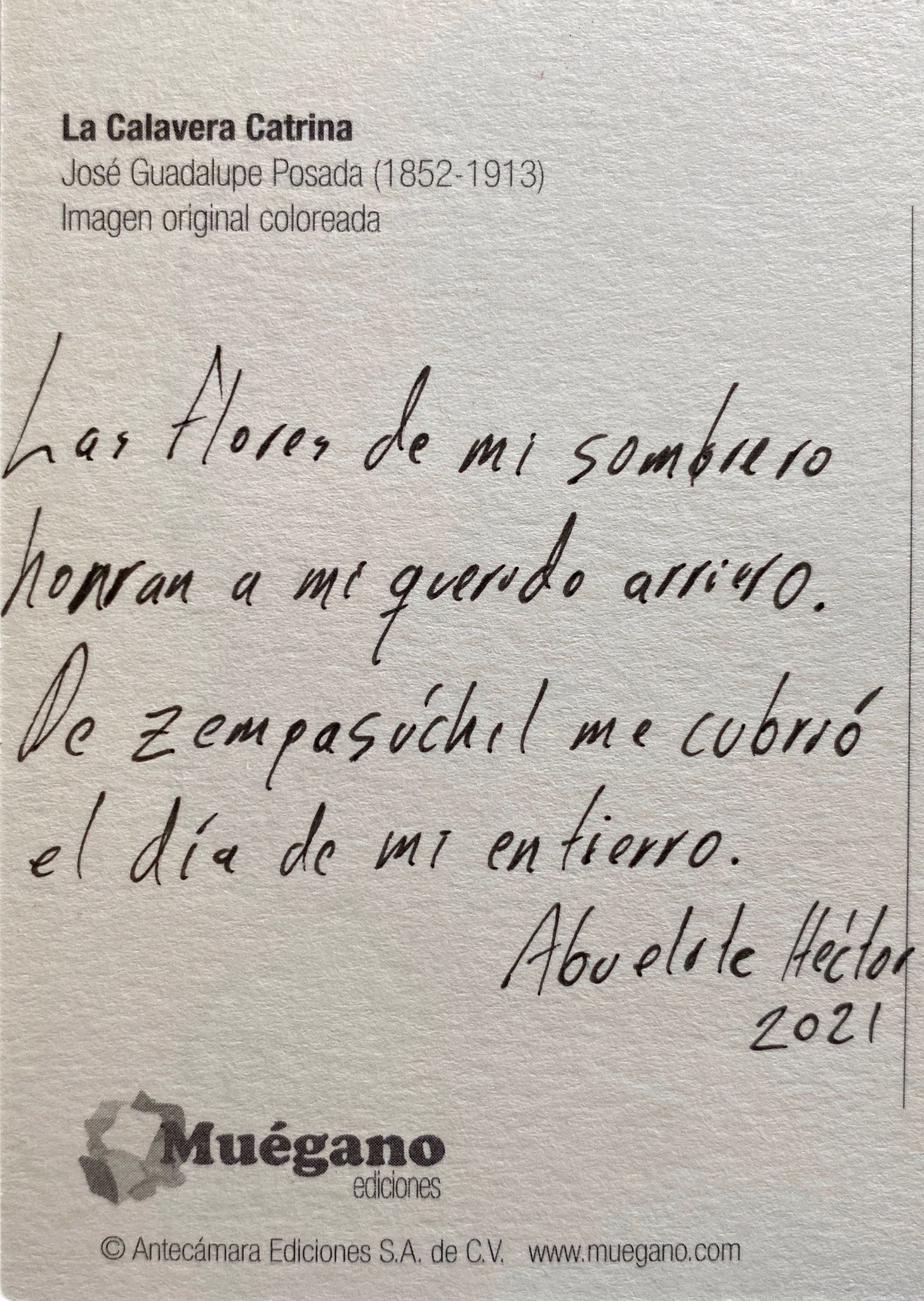

Las flores de mi sombrero

honran a mi querido arriero.

De cempasúchil me cubrió

el día de mi entierro.

Translation to Enligsh:

The flowers in my hat

honor my dear muleteer.

Of cempasúchil he covered me

the day of my funeral.

10

Este aguardiente bendito

lo uso para olvidar.

Mi dolor, un grito inaudito.

Maldecido a vagar y vagar.

Translation to Enligsh:

This blessed firewater

I use it to forget.

My pain, an unheard-of cry.

Cursed to wander and wander.

11

Descubrí a mi hermano gemelo

solo después de mi muerte.

Ambos morimos en un arroyuelo.

¿Quién creyera nuestra suerte?

Translation to Enligsh:

I discovered my twin brother

only after my death.

We both died in a stream.

Who will believe our luck?

12

Solo aprendi la guitarra

después de mi deceso.

¿Mi favorita? Pat Benatar.

Su catálogo está grueso.

Translation to Enligsh:

I only learned the guitar

after my death.

My favorite? Pat Benatar.

Her catalog is dope.

13

Emiliano nunca murió.

Está libre, en nuestras mentes.

Aunque por balas sufrió.

Su lucha eterna, vive por siempre.

Translation to Enligsh:

Emiliano never died.

He is free, in our minds.

Although by bullets he suffered.

His eternal struggle, lives forever.

14

¡Qué belleza es el tamal

!Historia envuelta en hojas.

Deliciosa nube de nixtamal,

manjar para todas las bocas.

Translation to Enligsh:

What beauty is the tamal!

History wrapped in leaves.

Delicious cloud of nixtamal,

delicacy for all mouths.

15

Un ratón, el pulque nos dió.

Un hombre lo fermentó.

Un pueblo lo disfrutó.

Una nación lo adoptó.

Translation to Enligsh:

A mouse, the pulque gave us.

A man fermented it.

The people enjoyed it.

A nation adopted it.

16

En vida nos amamos,

más juntos no pudimos estar.

Ahora muertos bailamos

por los besos que no te pude dar.

Translation to Enligsh:

In life we loved each other

but together we could not be.

Now dead we dance

for the kisses that I couldn't give.

Héctor González (he/they) is a queer nonbinary México-born speculative writer living in Austin, TX. They pair their love for food with their passion for stories and finding more about the secret origins of your favorite dishes. You can find their latest thoughts, cooking and writing as @mexicanity on Instagram, Twitter and Medium. Their motivational ASMR 4 Writers recordings can be found under Abuelita Héctor on SoundCloud (https://soundcloud.com/abuelitahector/).