In Winter, A Wedding: a poem and an interview with Sara Norja

I invited Sara Norja to read her Worlds of Possibility poem, "In Winter, a Wedding" and to talk to me about her creative process.

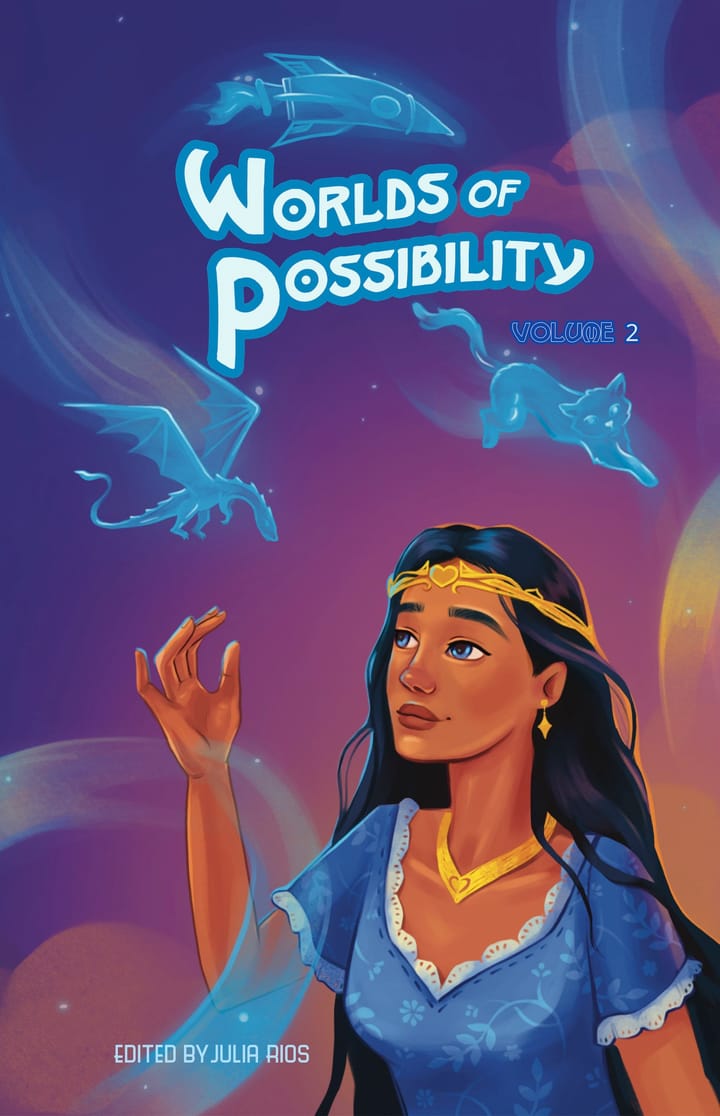

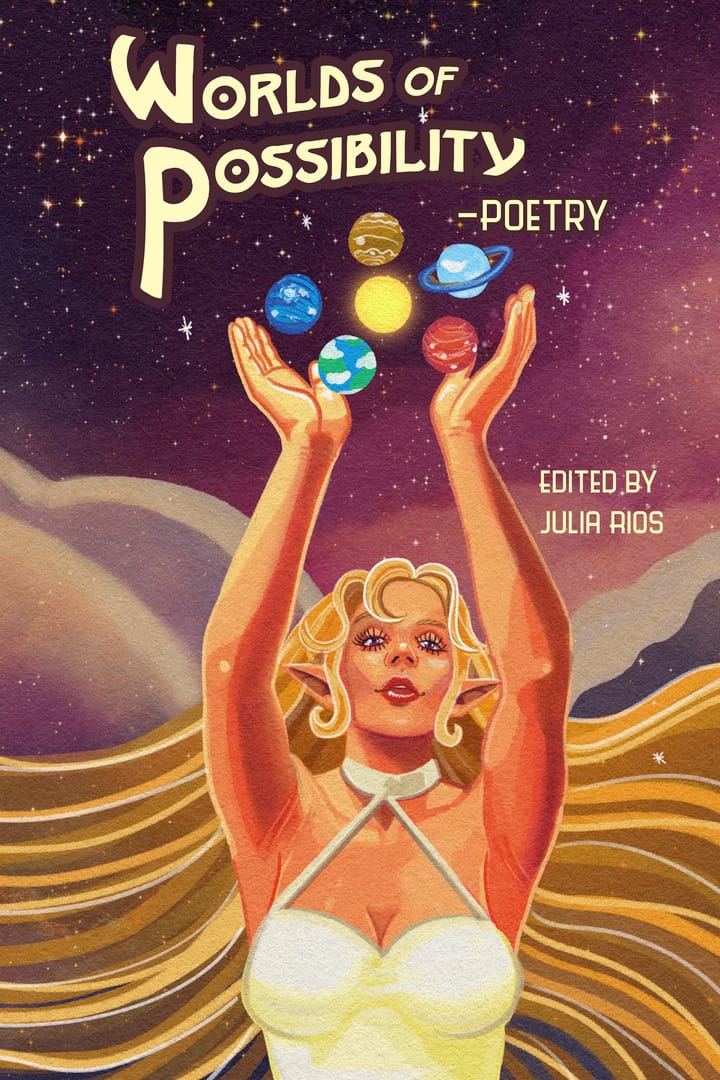

I invited Sara Norja to read her Worlds of Possibility poem, "In Winter, a Wedding" and to talk to me about her creative process. You can listen to the podcast and read the transcript of the interview and poem below. You can find the poem alongside many other poem in the ebook and print volume, Worlds of Possibility —Poetry.

Eliseeva Elizaveta, who created the illustration for this poem, is an artist from Ukraine. You can find more of her work on Instagram where she is @eeva_veta, and on Behance at https://www.behance.net/eliseeva96veta

Sara's Website: https://saranorja.com/

Sara on Instagram: @suchwanderings

Sara on Bluesky: https://bsky.app/profile/saranorja.bsky.social

This free podcast has ads. If you are a paid subscriber, you can listen to the ad free version at https://www.juliarios.com/ad-free-podcast-of-sara-norjas-poem-and-interview-just-for-paid-subscribers/. Patrons can also listen to an ad free version on Patreon at https://www.patreon.com/posts/14734217.

Listen to "In Winter A Wedding a Poem and Interview with Sara Norja - 1:3:26, 4.09 PM" on Spreaker.

Julia: Hello and welcome to the OMG Julia podcast where we discuss creative lives and processes. I'm your host Julia Rios and today I have with me a poet whose work was featured in Worlds of Possibility, Sara Norja.

Welcome, Sara.

Sara: Hello, Julia. It's really lovely to be on this podcast. Thanks for inviting me.

Julia: I'm delighted to have you, and you're going to read to us your beautiful poem and then we're going to have a little Q&A afterwards.

Sara: Yay. Awesome. So I'll get started. This poem is called "In Winter, A Wedding" and it's got several parts. So I'm just going to read the part numbers and their names and you'll catch up.

In Winter, A Wedding

1. The Magpies

Come, follow our chattering

feather-strewn way.

Snow lingers, winter’s fingers

are still clenched

around this land.

But stranger, never fear

winter’s cold – tonight

is a wedding-night.

2. The Stranger

The trees’ gentle filigree

of branches blossoms

against the crimson-as-anger

sunset sky

(crimson as my eyes

a year-and-a-day ago when

my truelove left me

and my memory stutters –)

The magpies lead me

to a farmhouse, abandoned,

dwarfed by the great stone

standing still before it.

I hesitate behind

the flurry of outlandish guests

warbling and whispering.

What wedding this?

A stranger congregation

of guests I’ve never seen:

sparrows and blackbirds

and owls beyond counting:

barn owls, little owls, owls with tufted ears,

tawny owls. And among the birds

fair-folk all a-shimmer

in their dizzying guises

of gossamer. Their ember eyes.

Whose wedding? Whose?

3. The Prince of Owls

Tonight the fearsome Lady

of Darkness shall claim me

for her own. How I long

for my truelove! but she

is forever lost, all memory

of me dimmed. My curse

obscures me. As tawny owl

I’m doomed to flutter

these winter lands.

Had I the power

I’d curse the Lady

for tricking me like she did,

but I have no magic

save that which binds me.

My hour of transformation

draws near, but before

I become a man (once a year

on the day of my cursing),

I’ll be married, forever locked

into this feathered form.

4. The Lady of Darkness

Truly, an owl

shall suit me well as husband.

A feathered addition

to my collection!

He’ll hunt for me,

claw my enemies’ eyes out.

Mine to keep. Soon. Soon.

5. The Oath-stone

His hands were on me, swearing fealty to his truelove, that day when the curse fell upon him with the rage of feathered things. Sundered from his family, from his truelove, from the world he’d known, he screamed as hands turned to wings, as feathers sprouted and javelined through his skin. Prince, the owls named him. Dead mice they gave him.

6. The Faerie Officiator

Up onto the oath-stone –

let the marriage-rites begin.

Here the bride, a cloud

of mist around her,

her eyes wolf-yellow.

Here the groom, still

as a tombstone effigy,

eyes round, feathers flat.

I clear my throats. Twin-voiced, I utter:

“We’ve gathered here

at the Oath-stone to witness

the joyful marriage-rites

of the Lady of Airless Climes,

she of many names (all of them dire),

and the Prince of Owls.

Before their hands are joined

in matrimony...”

7. The Prince, Eyeing the Crowd

I avoid the Lady’s glance.

My bird-eyes are sharp

as a whetted spear, and there –

Among the crowd

of birds and fair-folk –

a human, puzzled.

My owl’s heart

flutters. It’s her.

Eleri. My truelove

here. How?

Magpies dance around her, wink at me.

But it’s too late. How could she

break a spell she cannot see?

8. Eleri, No Longer a Stranger

An owl and a fay-woman:

a strange marriage the magpies

called me to witness!

The owl’s staring at me

with those dark-pooled eyes

as if we were old friends.

As if a lock

placed deep inside me

were clacking open

turned by an unseen key

9. The Officiator, Interrupted

The words patter from my mouths

familiar, the marriage-spell

from Her kingdom beyond the veil.

“I shall bind you two

in a covenant

unbreakable. If any

in this congregation

give objection, speak now –”

I never expected it. No one

dares cross the Lady.

But a shout rings out

in the winter air,

brittle as first-frost –

10. Eleri, Understanding

“I object!”

The words ring out

before I’ve realised

they were mine.

But why

do I object?

The fair-folk stare, baleful,

the birds are restless.

I’m trembling, stomach clenching

but the unseen key

twists. Opens up a memory

that was wrested from me.

Yes. My truelove was cursed

into owlness. He can’t marry

this faerie queen,

not before I’ve heard

from his mouth

that he loves me no longer.

Heedless, heart-sore,

I run to the bridal pair

leaving a fluttering of feathers

and shuddering of cobwebs behind me.

The owl hoots, his eyes alien.

But I remember him.

“The prince of owls

is under enchantment

and cannot consent. Free him!”

11. The Lady of Rising Rage

What

does this human girl

think she’s doing?

I scream at the officiator

to continue her spell-words,

for I want this prince

to grace my halls.

The officiator shakes

her heads. “She objected.

Law must run its course

even in Faery.”

I care not for laws.

I am my own law.

I want this marriage

and no human wench

can stop me.

12. The Prince, Constrained by Feathers

She remembers.

She remembers, but even that

is not enough to break the curse.

13. Eleri, Breaking

Mad gleam in the Lady’s eyes,

her fingers spinning a spell.

I should fear her

but now that my heart’s door

has been wrenched open, now

that memories have drenched me

with their sunfire, I can’t

hold back.

The prince of owls

flutters to my outstretched arm.

“How do I break the spell?”

“To-whoo,” and grieving “to-whoo!”

If he knows, he cannot tell.

Desperate, for the Lady

has murderous magicks

up her gauzy sleeves,

I summon all my strength:

change. change. change.

He doesn’t change.

14. The Birds, an Army

The Lady of Darkness

is threatening our own,

our Prince of Owls.

We fly – to attack,

a beating of wings

and gnashing of beaks –

15. The Lady, Disgusted

Oh, sod it all.

I’ve had it with birds,

dirty stinking things

ripping my sleeves to shreds!

This marriage isn’t worth

such indignity.

Come, my people!

Let’s away to Faery

and calmer climes.

16. The Prince, Transforming

Then the pain screeches through me.

Wings become arms,

feathers fall away

as a cloak around me.

Beak becomes nose, and my eyes

turn over in the darkness. I can’t see.

“Eleri, come to me!

Were we married now

we could break the curse.”

17. The Oath-stone, Shuddering

An opening of the land: the fair-folk depart. On the heels of their leaving it comes, the time of change, the moment when day becomes next, when an owl becomes a man for one day a year. Who will witness this marriage? Who officiate the rites? I’m cold stone, speechless, muttering to myself in three languages. Yet I witness. I witness.

18. Eleri, Breathless

Him. Transformed. I swirl my cloak

to cover him. Hold him close,

his human self dizzying

after so long apart.

“Marry me, my love.

Let this oath-stone be our witness.

Let the smallest owl officiate.”

The stone’s silent in the darkness.

The smallest owl hoots his last.

We’re married. I think.

Tomorrow will tell

if the transformation’s true.

If my love becomes owl

with another day’s turn,

well, we’ll wait another year

for now I’ve found him.

19. The Prince, No Longer of Owls

I trace her jawline with my human hands,

hold her close with human arms,

whisper to her with human voice.

We walk towards the dawn and our future.

20. The Magpies, Chattering

We couldn’t guarantee her

happiness. But we pushed

and she took to the air,

her deeds like wings.

The End

Julia: Ooh, I love that poem so much.

Sara: I really like it too. It's really fun to read.

Julia: All right, that was "In Winter, a Wedding" by Sara Norja. That appeared in the February 2024 issue of Worlds of Possibility. And it is, as of the broadcast of this podcast, also now up for free online, accompanied by an illustration by Eliseeva Elizaveta, an artist from Ukraine. So if you go to juliarios.com or follow the link in the show notes of this podcast, you can see the illustration that goes with it as well as reading the entire text.

Sara Norja writes in two languages. She was born in England and lives in Helsinki, Finland. Her English short fiction and poetry has appeared in venues including Goblin Fruit, Lackington's, Fireside, and Strange Horizons. Her works in Finnish include a nonfiction book on alchemy, and a queer verse novel. Sara is @suchwanderings on Instagram and saranorja.bluesky.social on blue sky. Her website is saranorja.com

And we'll have the links to all of those in the show notes and on the website as well. So you can certainly go check out her other work, which I absolutely recommend. It's beautiful. And if you love this sort of mythical fairy tale vibe, it's absolutely for you. So luckily we have Sara here to talk to us a bit and answer some questions today about her creative process.

Sara, before we get into any bigger questions, how did you get into writing in the first place?

Sara: It's a kind of traditional origin story because I've really wanted to become a writer since I was five years old. So basically since I learned how to write, I think I found out that some people actually write the books that I love to read or have read to me, and I wanted to do it. My other option at age five was to become an opera singer. That never happened, but the writing part definitely has been a thing. So I think I've just always really been very interested in telling stories and especially telling them through the medium of writing.

I've got way too many notebooks from throughout my life just... documenting all of my various attempts at writing of all sorts. My first so-called novel, which is one whole tiny notebook in length, was basically Aladdin fan fiction for the Disney movie. I was convinced I was very original, but it was Aladdin fanfic, but it taught me a lot. I learnt how to use punctuation during that time, so that was very useful.

Julia: Aladdin fanfic. That's a that's a good one. I think that most people start off by writing something that is sort of, whether consciously or not, fanfiction of something that they have loved. We tend to imitate styles and stories.

Sara: Yep, absolutely. You can basically see a lot of what I was reading in whatever I was writing at the time, especially obviously before I was in my 20s and started to actually develop a style of my own. It's like a catalogue of everything. You could definitely tell when The Lord of the Rings came in because I started using very fancy words that I didn't really properly understand, but I wanted to sound archaic because, you know, obviously... but yeah, there's a lot of of influence from various things and I still enjoy it, obviously. Like I'll be influenced by whoever's style I'm really into at the moment.

Julia: I think that's very common. I think that it's really common for people to be taken with a style and then kind of try their hand at it.

Sara: Mmhmm.

Julia: I think you see that all across art movements as well.

Sara: Yep.

Julia: I don't think you get the impressionist movement without a bunch of people being like, oh, that's interesting. Let me try it

Sara: Yep. And I really love that that's how a lot of really cool things happen. And I love it when I can be inspired, for instance, by a poem that a friend of mine wrote or something and just be like, oh, well, what would this be like if I did it? But it's like my style. And that's just a lot of fun.

Julia: Yeah, I love that.

Sara: Yeah, intertextuality is just great.

Julia: I love the conversation that creative things have with each other.

Sara: Yep, absolutely.

Julia: So let's talk a little bit about this specific poem. Where did you draw the idea from for that?

Sara: I wrote this poem quite a while ago, and I just had not really ended up submitting it to places because it was of a far longer length than a lot of places will will accept, but when I wrote it, I remember just being very struck by the image of of the Oath-stone as a sort of wedding officiator, and just this whole notion of transformation, which is something I love. I feel like a lot of my work is about some sort of transformation, which is obviously not very original, but transformations are great. And I especially like humans transforming to other animals. That's just always a lot of fun. So I think the original idea was basically around this weird Oath-stone talking, and then I started to gather up the various narrators.

I feel like the the story of this poem itself is obviously a very kind of basic fairy tale, a sort of Tam Lin inspired thing with the fairy queen wanting to take someone as her husband and, you know, he doesn't want it. There's a girl who tries to stop it. I think there was some kind of Tam Lin thing going on in my brain, probably subconsciously, because I don't remember really thinking about it too deeply, but I really like the legend of Tam Lin, so something of that came in. And then because I really enjoy doing things with form, I really wanted to try having... I think at first I tried to have every bit of the poem with a different narrator, and then I realised I'd need to repeat some of them, but with the different sections are obviously all named slightly differently. So even if it's the same narrator, it's a little bit, something about the tone is is a bit different in the little titles of the sections. So I kind of managed to keep some of that changing narrators thing that I wanted to go for when I was writing this.

Julia: Yeah, I really like the format of this poem. And I agree, it's a very traditional sort of fairy tale trope, the the animal bridegroom trope.

Sara: Mm-hmm.

Julia: But I think it stood out to me when I read it, when you submitted it to me, because it does have such an interesting style. I mean, first of all, your language is beautiful. So that helps. But also, I think all the different viewpoints, and especially having the viewpoint of the Oath-stone itself is really interesting and not something I would normally think that I would see.

But I also love that you have like the the viewpoint of the birds and you're also seeing sort of the the witch fairy queen and the owl man and the human bride, like all of them are having their own agendas which is really cool to see. It felt in some ways to me kind of like when you watch an old silent movie and they have caption cards that introduce a scene and they're like here's what's going to happen in this scene and then you see the scene and you're like yeah, that is what's happening in this scene.

Sara: That is such a charming idea. I mean, I feel like when I when I wrote this, it's like, okay, so the story is straightforward, but we get it told in a sort of fragmented way where the narrators sort of crisscross in some ways, and I kind of enjoyed that. Now that I was reading out again, I thought that I should write some more stuff kind of like this. In a way, I feel like I see something... Like, I wrote this poem long before I thought that I would write a verse novel, which I have done in Finnish. And actually, now looking back at this poem, I can definitely see the precursor to the sort of verse novel vibes, in that it's like I do play around with the language and I can use very poetic language, but also there is a plot going on. And that's clearly something I enjoy.

Julia: Yeah, there's very much a long, overarching plot. So tell me about your writing process. You were born in England, but you live in Helsinki. You're fluent in both English and Finnish, and you write in both languages. How do you choose which language to write in and what type of thing you're writing?

Sara: That is a great question because it actually really depends on what I'm doing. Like, for instance, the verse novel that I've had published in Finnish, it's called Kummajaisten kesä, which I think I translated somewhere as The Summer of Strangelings. Not quite the same thing because kummajainen in Finnish can also in some ways be a sort of very archaic term for a queer person. So there's a lot of layers that you don't really get by translating that. But when I started writing that, it's a novel that is extremely tied to my own experiences at Finnish summer cabins and the sort of weird magic that happens in Finland in summertime when you're in a cabin by the lake and there's a lot of trees around you. And that was not something that I could really imagine writing in English. Although I'm considering trying to translate that just because so many of my non-Finnish speaking friends have wanted to see it. So we'll see if that's even possible. I'm going to give it a go.

But usually I feel like when I start out writing, I will have a feel for what language this thing is going to be in, and quite often it's because there's something in either the subject matter or just what I want to do with the language that calls to me in either language.

So, for instance, I'm currently also revising an epic fantasy novel in English, and I couldn't write that in Finnish. Partially because there's not a similar market for epic fantasy in Finnish at the moment, but also it's the sort of novel that I just feel needs to come out in English. It's a novel about empire. There's a lot of things about that, which obviously with English being the sort of global lingua franca and my own complex feelings about basically kind of being somewhat culturally English, but I was born to Finnish parents. I am very Finnish as well. So there's a lot of that sort of feelings. I feel like just writing about empire in Finnish would feel a bit strange when I can write about it in English.

So it's often quite determined by the subject matter and also somewhat the form. Like I'm now considering writing another verse novel in Finnish, mostly because I really enjoyed that form in Finnish in particular. Somehow Finnish works really nicely — you can get a lot into a single word or a line. It's easier to pack stuff in compared to English because of just the grammatical structures of the language, for instance. So it's somehow easier to think of doing certain things in a certain language.

Julia: Okay, so you mentioned the difference between language structures in English and Finnish. And I think I've heard this before, and I'm not exactly sure, but that drabbles are more popular in Finnish, like a hundred words exactly, because you can do a lot more with the language

Sara: Oh, yeah. Absolutely. For Worldcon, back when Worldcon was in Helsinki in 2017, I was on a panel about drabbles, which was a bit hilarious, because even though I'd written quite a bit of flash fiction at the time, I hadn't really written too many exact 100-word drabbles. So, you know, I wrote one in Finnish and then I translated it into English and it was really hard to get anything like the same amount of information in because Finnish is a language that, you know, a lot of the grammatical endings and things that in English we'd need several words to convey, like prepositions and things, in Finnish, they're just basically grammatically mashed into the same word. So when you count things by word, you can actually get away with a lot more substance. And this is also why Finnish publishing doesn't tend to... like, for instance, my book contracts are not by the word, they're by the character, because words can vary a great deal in length in Finnish.

Julia: That's fascinating. So they pay based on how many characters are in it because your words get longer, I guess, as they get more complex?

Sara: Yeah, so basically the book on alchemy that I wrote a couple of years ago was, I think my character limit was around 500,000 characters. And the book is 300-ish pages as a hardback. So it's just like easier to easy to estimate things in characters in Finnish. And I admit I sometimes struggle with that because I'm just so used to estimating things according to word count in English, but it definitely makes more sense in Finnish to do things according to character count.

Julia: So tell me about when you were growing up and the languages that you spoke, how did you kind of learn both English and Finnish? Did you live in England for a long time? Did you have school where you learned English? Did your parents speak Finnish to you at home? What's your story there?

Sara: Yeah, so kind of a, in some ways, typical-ish child of immigrants experience. So my parents already lived in London. Well, actually, they didn't live in London at the time. They lived in England when I was born. And then my sisters were also born in England. And we lived in London for most of that time um until I was about 10 years old, almost 10. So I had a lot of formative experiences in England and sort of through English.

I have one memory that's a very vague one from the time before I really knew English, and I think it's from like a daycare that I went to. Because I remember the time when I was left there by myself and my mum, you know, went away for the whole few hours that I was in the daycare. I remember just going and like speaking some Finnish to myself wrapped up in my coat in the cloakroom because I was just so overwhelmed by the English around me that I couldn't really understand yet. But the next memory I have is of me dancing the hokey-cokey and singing English along with everyone else. So I think it's fair to say I learned pretty fast.

I think I was about, probably about three years old when I learned English and, you know, just acquired it through through being being in daycare and then later in school. I started school when I was five and I apparently was very shy at first, but then I couldn't shut up once I got over the shyness. So that's kind of how it's gone since then.

Julia: Yeah, I feel like my school reports were pretty similar. Like, yeah either I'm very quiet or I'm way too talkative.

Sara: Yep, yep, yep. It was me. Like, I think my parents got a report where it's like, it's great that your child speaks English fluently, but also could she maybe shut up for a moment?

Julia: She should not speak English as often in class...

Sara: Yeah, she just needs to keep a lid on it.

But yeah, so my parents spoke Finnish to me and my sisters. And we were also in the sort of rare situation where we actually lived in a sort of mini Finnish community in London. My dad was the rector at the Finnish church in London, so we had a sort of Finnish environment there as well. So Finnish was kind of the home environment and around the church. And then English was everywhere else. But my sisters and I soon started speaking English together when we were playing. Like we'd do the typical bilingual thing where you just code switch between languages depending on what you need to say, how you need to say it and so forth. And we still do that. Like it's a very bilingual family basically ever since, even if Finnish is the main thing.

Julia: So when you are thinking back to your childhood and you're thinking about like books that you loved to read, were there different kinds of books that you would read in English versus in Finnish?

Sara: I mean, kind of, mostly depended on what we had. So I feel like I've read most of the sort of English classics that any child in England in the nineties would read. But then in Finnish, we probably had more of the sort of absolute classics of like Finnish children's literature. We had a load of books though, because my parents, especially my mum, was really into reading and books forever. And I think she's the main reason why I became very obsessed with books. But I think we just got sent a lot of books by family back in Finland as well. And we would scour all of the secondhand bookshops in London to find reading for me and my sisters. So I feel like there wasn't really a huge difference when it comes to what kind of things we were reading. It's more what was available because I would read everything.

And especially out of the Finnish books we had, funnily enough, I really, remember mostly enjoying things that were actually originally translated from Swedish. So books by Astrid Lindgren, like Ronja the Robber's Daughter and Brothers Lionheart, I think it is in English. So these sort of classic, basically kids fantasy. But they felt very Finnish because Sweden and Finland are similar enough in culture that there's that whole Nordic vibe going on.

Julia: Right. So were you always drawn to the sort of fairy tale and mythic stories?

Sara: Oh, absolutely. I was always very obsessed with with all of that. Like I liked a lot of different things, and you know when I was a kid, I enjoyed stuff like school stories, boarding school stuff, all of the sort of normal things as well, but I do think that I was most obsessed with fantasy and the fantastical even then. And like a lot of nerdy kids do, I had a mythology phase, or you know several mythology phases. I had a a few books on mythologies around the world, so very obsessed with reading everything about whatever mythology I could find. Egyptian mythology, amazing. Norse mythology, Viking mythology, yes. I was very into Celtic stuff and, yeah, just anything I could find, really. Greeks, Romans, all of it.

There wasn't that much available at that time on Finnish mythology. So that's kind of come a bit later. And there's still a lot that folklorists are doing about actually what Finnish mythology even is and stuff like that. It's not just the Kalevala, which has a very complex history. so But yeah, I was obsessed with fairy tales from a very young age, basically.

Julia: Okay. And so then you went into an academic sort of career where you're writing these nonfiction books. How did you decide on your specialization, and what makes you decide the topics that you dig into there?

Sara: So basically my specialisation has come a lot from my academic interests. So in my academic life, I study the history of English and I've been particularly interested in studying the history of scientific language. And thus I went to study alchemy, which may not make sense on the surface, but alchemy — it's like my pet peeve that alchemy, in the Middle Ages especially, should be considered as a science because the people of the time saw it that way. So even though it has a lot of features that we would consider magical and not at all scientific, people viewed it as a science, so that's how I feel medieval alchemy should be viewed.

So basically I got very into studying alchemy during my PhD research and I realized that I was actually very interested in writing about it for a non-academic audience as well. And there's a lot has been written on alchemy in English that's more popular. For instance, Laurence Principe has this great book called The Secrets of Alchemy that was one of my inspirations for my my book in Finnish.

But basically, I discovered that there wasn't really anything proper on alchemy in Finnish. So I kind of went that route of... I'd done a lot of research for my PhD introduction that definitely didn't belong in a PhD introduction because it was all way too long. So I ended up putting all of that in the nonfiction book. And for a while after I'd finished that history of alchemy book, I was in the possibly typical way of, you know, first time nonfiction author going like, oh, I don't know, maybe I just don't know enough about anything else to be able to write about it, which is, it's the inner academic in me because I feel like, oh no, I haven't done a PhD in it. I can't write about this.

But now, turns out, I've got a lot of nonfiction book ideas, and they basically stem from partially stuff that I actually do research on an academic level and write peer-reviewed articles about. But, for instance, the book that I got a book contract for very recently is about the history of fairies around the world, and that is basically just me wanting to get nerdy about something I've been obsessed with in a non-academic way for all my life. I feel like I'm now at the point where I have enough research skills that I can basically take a topic that interests me and I'll probably be able to write something sensible about it if the topic hasn't been super overdone. And there's a really good nonfiction book scene in Finnish. Finns really love reading nonfiction. But there's also a lot of topics that just haven't written been written about that much yet because the publishing industry is so much smaller in this, you know, well, it's not a small country as such, but it is a very small language area. So there's just way less stuff getting published. And thus people like me can somehow get to write about fairies, which is incredible.

Julia: Oh, that's awesome. So when you are going to write this book, are you planning to write things about fairies in Finland or just about other places in the world?

Sara: My current problem is that I need to grapple with the question of what is a fairy. I somehow thought it would be simple. And then I started thinking... Because, I mean, the plan for the book currently does include a chapter on Finnish fairies because I do think that some creatures from Finnish folklore can be called fairies if we're using a sort of broad term. And I do want to use a very broad definition of fairy in my book. I haven't yet quite figured out what the definition is, but basically I feel like there's a lot of creatures around the world that can be seen as a type of fairy. And I don't want to think of fairy as just the sort of very Anglo type of creature, but as just like a mythological creature that's not a god and not a ghost and not a demon, but it's something in between some of these things. But I'm definitely interested in writing about the Finnish context as well.

For instance, there's a creature in Finnish folklore that's kind of, I think, been brought here by the fact that we were part of Sweden for a very long time, so it's also similar to Swedish folklore, about this creature called the Näkki, which is basically a sort of fairy who plays the fiddle next to a body of water, like a stream, and will either teach you how to play so that you're the best fiddler in the entire universe, or then possibly drown you and that kind of fae stuff basically so I feel like the Näkki is extremely fae but as to whether some other Finnish folklore creatures are, that I will have to find out.

Julia: Right.

Sara: It's a really interesting problem, and I kind of love that part of my job is thinking about the ontological like concept of what a fairy even is, but it's not easy.

Julia: Yeah. So I know you have a novel in verse and finish, but do you mostly write fiction in English?

Sara: Quite a lot of the time, yeah. I have written some short fiction in Finnish, and I have a couple of longer projects planned in Finnish, but I do feel like my novel brain is probably a bit more English than Finnish, which is kind of funny, because maybe 10 years ago or so, I remember thinking, I can't really write poetry in Finnish. It just doesn't somehow feel right. And then now I feel like a lot of my poetry comes out in Finnish and the verse novels feel like they really work in Finnish.

I have clearly got the nonfiction in Finnish. That's working out fine. Verse in Finnish, that's working out. But I feel like I'd still need some practice in finding my long form fiction voice in Finnish, whereas I feel like in English I've written enough novel drafts to kind of have have some inkling of that.

Julia: And do you think that people in Finland read in English a lot?

Sara: Yeah, people do quite a lot, especially in SFF. A lot of the newer stuff has now been translated more than it used to be. For instance, there's this really great publisher called Hertha that has translated Murderbot, for instance, which is very cool. And they've got a translation of This Is How You Lose the Time War, so some of the more sort of current SFF is being translated, but I feel that if you're a science fiction and fantasy fan and you live in Finland, you kind of probably do want to read in English because otherwise you won't find a lot of the stuff and you'll run out of of stuff to read in Finnish, in terms of stuff that's coming out translated. But there's a really great Finnish science fiction and fantasy scene. So there's a lot of writing in Finnish as well, especially from smaller publishers.

So basically people definitely do read in English, but I think a lot of people do the thing where even if they read very competently in English, they do also prefer to read in Finnish just to get all of the emotional nuance and so on. And that's something where I've got the unfair advantage of being bilingual, because English, Finnish, both of them give me the same... Well, they're not the same emotional vibes, but I get deeply emotional in both languages. So it's easy for me.

Julia: Right, so you can easily think in both languages and don't have...

Sara: Oh yeah, and at the same time, on top of each other, etc.

Julia: I think that it's harder if, even if you understand a language, if you're constantly kind of doing the translation in your head, then it takes away from the ease of reading and getting immersed in the experience of the story.

Sara: Definitely. Like, I read in Swedish to some extent, and my Swedish is pretty good, but it's more of a struggle to get immersed because I just need to work on what this word actually means, or did I grasp the grammar right, you know, and I'm sure I'm missing a lot of the nuances that Swedish speakers would find.

Julia: Right.

Sara: But that's, you know, I just really love sometimes reading in the original language and I would love to do it more for languages that I've learnt in the past even though I also really appreciate translations because I also do some translation as a side gig occasionally and it's really hard especially for fiction so I salute all of the people who translate SFF especially because coming up with all of the concepts and how to deal with you know various gender things for instance, that's not easy in another language.

Julia: Right, because gender works differently in Finnish linguistically.

Sara: There was a discussion somewhere about some people disagreeing with some of the translation choices made for Murderbot for instance, just in terms of because there's some neo-pronouns for some of the characters in it, and I feel like in some way in Finnish you wouldn't really need the neo-pronouns because Finnish only has one third person pronoun, han, or seh if you're in colloquial language, so you kind of don't even need that sort of distinction like you would in English. But that's, again, that's a translation choice that I'm glad that I don't have to make because... very difficult call. How do you... because I feel like especially Murderbot, you don't necessarily get other indications of gender apart from a pronoun. So what are you going to do as a translator if you somehow want to indicate that this person is, for instance, non-binary in some way?

Julia: And how does that affect actual people in Finland presenting? Like if you are a non-binary person in Finland, to do you present differently?

Sara: I mean, it's easier in some ways, I feel like. I'm cis myself, but I've got a lot of non-binary friends here in Finland. It's easier in some ways because, for instance, you don't need to let people know about your pronouns if you're talking Finnish because we've all got the same pronouns. But that can also, in some ways, make it harder, I think, to come out in a sort of subtle way as non-binary. If you introduce yourself to someone in English and you say, "Hi I'm so-and-so, they/them," that kind of definitely gives an indication, but in Finnish like it's it's harder like you'd have to do it through non-linguistic means through your like presentation or something so I feel like there's that.

And even though Finnish like as a language is not necessarily as aggressively gendered as some some languages, certainly there's still a lot of the binary just within the language. like A lot of things just have a sort male-female thing, even if it's not as as obvious as in some other European languages, for instance. So it's difficult in different ways and less obvious in different ways. Like, I don't know the pronouns of a lot of people I hang out with and sometimes I need to ask them, "Hey, so what are your pronouns in English? Because if I talk about you to someone else, I don't want to misgender you, but, like, what are your English pronouns?"

And a lot of Finns actually... like I feel are more on the meh side of pronouns. Like If Finnish is your native language, even if you're non-binary, you just may not have that strong feelings about pronouns because they're all weird. And like a lot of people will have will struggle if they're not very fluent in English. They'll just struggle and accidentally misgender people just because even just he and she are kind of foreign. It's a hard distinction.

Julia: You don't have it. It's hard to tell what you're doing. Does that translate to, for instance, gender roles and the way society views what people do?

Sara: I mean, we do still have a lot of the basic nonsense that all of western society probably does with regard to gender. I think mostly in Finland there's a bit less of the sort of very stereotypical oh women can't do this blah blah blah blah thing possibly because we were a very agrarian society for a long time, and in agrarian societies, the farm wife will be a position of some power and she's got a lot to do and she's certainly not the sort of like, you know, "Oh let me get my smelling salts," kind of feminine person.

So, you know, I feel like a lot of Finnish gender presentation and just thoughts about gender kind of come from just having a sort of slightly more agrarian view on this. But that said, there's a lot of of stuff, and especially these days, we've got a very right-wing, like, bordering on fascist-ish government currently, so I think there's a lot of thoughts on people going like, oh yeah, back to traditional gender roles, and it's like, yeah, but I don't know if we really even had those in some ways, and definitely don't want to go back to that, whatever it is. But yeah, it's not as as utopian as you might think based on the language, unfortunately.

Julia: Well, I mean, we all have room for improvement, I suppose.

Sara: Oh yeah. And I mean, we we continue to fight the fight.

Julia: Indeed. So speaking of fighting the fight, I feel like a lot of times people say that one of the things that does drive sort of progress is the fiction that we read. Is that something that you think about when you're creating? Or do you just kind of tell the stories that come to your heart?

Sara: That is a lovely question. I'd say it has been driving me more in recent years, because, for instance, I've got way more anxious about the climate in recent years now that it's been possible to just observe in real time what the climate catastrophe is doing. And, you know, I've been anxious about the climate since I was like 14. So it's been a while. But I do feel that that, for instance, does drive some of the stories that I want to tell, even though a lot of stories I've got in my mind are things where I just want to tell this cute romance, like, this is just a fun story. Like, the things I've been writing recently have definitely been more on the, "Welp, let's topple this empire, shall we?"

I do feel very affected by the fiction that I read. And, like, for instance, if I read about a fictional revolution, I feel more galvanised to do some stuff in my life. I feel that there's not a lot of things that I can do personally that are very useful to a lot of the causes that I fight for, unless it's me going out onto the streets. So I feel that if, with my art, I can at least somehow maybe change someone's mind a little bit, make them think a bit more about something, make them question the world and whether these structures are actually that good, then I really want to be part of doing that.

So even though for me, fiction is about the story and I don't want to write, you know, preachy fiction. I think everything is political, and you know I will always write political things, but I don't want to have my fiction be reduced to just a manifesto. So I also want it to work as a story with beautiful words. Stuff like that. But it is important to me to have that somewhat activist mindset to it. Even if it's a beautiful poem about fairies, it can contain something that could change someone's mind.

A lot of who I am is formed through what I read, and I'm pretty sure I'm not alone, so I think it's important to write things that can also be part of activism.

Julia: Yeah, I would definitely say that that's true. And I think that a lot of stories that we love also have something at the heart of them that is driving them, even if they're not necessarily preaching about it. But you mentioned The Lord of the Rings earlier, and I feel like that has a lot in its heart about the horrors of war.

Sara: Yep, definitely influential, and yeah about the horrors of war and about the importance of coming together, even if it's against a seemingly impossible dark force. I mean, it's things that are kind of bread and butter to current-day epic fantasy, but I feel that there's there's a reason why that that story still has a big part of my heart, because there's just those those deep themes Like, you know, the the bit in The Lord of the Rings where the Rohirrim arrive and the horns ring, it makes me cry every time when I read it. It's just that sort of hope that comes from having acted towards something thing and then having it actually, you know, bloom the moment where you least expected it.

I feel those moments are so important to me because... keeping hopeful in some way is extremely hard right now in the and this stage of the world. So I feel we need we need all the help we can get.

Julia: Fair enough. Well, I think that I find hope personally in all of the creative people that I see around me who are still creating beautiful work even in times like this.

Sara: Absolutely.

Julia: So thank you for being one of them.

Sara: Aww, thank you, Julia.

Julia: And with that said, let's wrap this up and let's say that there's someone who the first introduction that they've had to you is this podcast. The first thing they've heard from you is your poem "In Winter, a Wedding." What would be a next thing that you would advise the first time reader to seek out?

Sara: I would actually very much go for my story in Giganotosaurus, which um is called "Reconciliation Dumplings and Other Recipes", which features some lake-dwelling demons and goblin bargains and overcoming prejudice, and it actually has a bunch of delicious recipes that work, because I tested them with my collaborator and partner, Jari Haavisto. They are actual recipes that you can actually use, and also there's a story. And I feel this also has some of that sort of... It has those vibes of being a very Finnish story, except it's in English. There's some stories that I've written in English that have very Finnish vibes, and this is one of them.

Julia: Okay, g0 check out "Reconciliation Dumplings and Other Recipes" in Giganotosaurus. And also definitely check out Sara's website. Follow her on social media. She's wonderful. Read all of her work. And Sara, thank you again so much for joining us.

Sara: Thank you, Julia. This was a real pleasure. Thank you so much.